The Inside Out View

In the usual organisation of theatre, the view from the technical booth is normally invisible to the audience. It offers a perspective that is not supposed to be part of the ‘public' aspect of the performance – an expectation undone only when something goes drastically wrong. In a production in which the division of space – producing a drama of both licit and illicit voyeurism – is fundamental to the design, it seems especially appropriate to put this perspective into dialogue with those of the reviewers.

Like the performers, after the opening party scene, no one audience group in Amato Saltone has a view of the whole show; and, indeed, given that the two reviewers were women, there is one audience viewpoint that they could never get to see – that of the group of segregated men. As it happens, this is one of the two views provided by CCTV in the technical booth, to help keep track of the progress of the performance. How can a review respond to this fractured dramaturgy, where the reviewer is normally expected to offer a synthetic perspective on the whole experience? In this instance, this question itself structures the project of the review. The view from the technical booth is itself further fragmented not only in space (being removed from the encounter between performer and audience), but also in time. Here, the performance is experienced in terms of cues: divisions of time into numbers that must correspond between the sound and the lighting systems to achieve a unified effect in that encounter between audience and performer, What links these two systems is a device that links computers called 'midi', and the performance text in the booth is punctuated by a regular, resigned note: 'The midi's down again' – at which point (twice on this occasion) the elements separate out and have to be synthesised manually rather than by the machines. One consequence of this, on the evening being reviewed, was that a series of cues for video projection was lost. Paradoxically, then, in the booth one can even see what is not visible to an audience during the performance.

The sense of the show in the booth as different in time from that of most reviewers is due also to the fact that it is not simply the one performance that is experienced, but rather its relation to all the previous ones. On this evening, there was the pleasure of experiencing one of the performers trying out something for the first time – in the event, something that was felt not to 'work' and which was changed again on the next night. Of course, this measure of ‘review' within the performance process by the company is not confined to the constant attempt to explore the possibilities of the show. It also extends to a sense of the audience – sharing the feeling afterwards not only of whether it was 'good' or a ‘poor' performance that night, but also whether or not they were a ‘good audience'.

Mischa Twitchin, a member of the Shunt collective

On Reflection

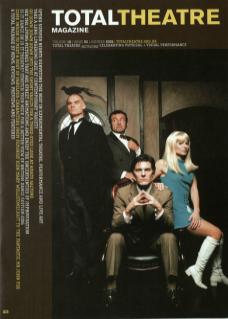

The long walk from London Bridge's bustle, through perilously under-lit caverns towards distant laughter from the fairy-lit troglodyte decadence of Shunt's bar, is a representative herald of the latest Shunt experience. Always focused on immersing the audience in a surreal, extravagant world, in Amato Saltone Shunt have married this preoccupation to thematic content through an exploration of the seedy noir lens of writer Cornell Woolrich. The pulp writer's fascination with voyeurism, intrigue and seamy melodrama proves an excellent foil to the company's unique style and setting.

From a participant's point of view, the unsettling, and perhaps slightly over-emphatic, feeling of being 'left behind’ by the rest of the group (siphoned off for the best part of the evening) was usefully unnerving. Creating an 'Other' through the split audience set ideas of surveillance and intrigue into play, galvanising our response to the work unfolding around us. Shunt's shtick is to progressively provoke an audience out of its complacency, this time gamely giving us characters later to be credited in the film of the show, and welcoming us to what rapidly emerges as a swingers' party, threatening participation. When the power is cut, we are led into a more disturbing communion with our fellow participants/witnesses – herded through the postures of unwilling voyeurs of disturbing acts, and becoming unwitting performers within the disorienting urban landscape created by the company. There's an effective and persistent sense of something occurring just off stage – a mole in our midst, a demanding voice on the telephone, a glimpse of our lost compatriots – and within the gloom of the vaults, a palpable crackle of anticipation.

At its best, the show plays skilfully with an audience hungry to consume: first empowering then rendering us vulnerable; involving us then rejecting us. This experience resists complacency and recreates in us the sense of simultaneous relish and unease at the emotional heart of Saltone. The performances are ingeniously worked out and the absurd sense of humour threading through the whole warms us to what we might otherwise resist, and enriches the characters we meet only fleetingly as they shepherd us through their environment.

It is difficult then to reassemble later the simpler experience of the audience when the performance resolves itself into a presentation of cinematic images in a split auditorium. Here, hilarious spoof noir, strange fetishistic acts and stylised quayside courtship combine to make the intriguing suggestion that previous acts witnessed were not only theatrical but also cinematic fictions. Yet this image-based sequence felt harder to swallow. Our relationship to the images – however beautiful, provocative or mysterious – was less engaging than our experience of being part of them ourselves.

This risk of disengagement threatened throughout the evening. In a show playing with the processes of looking – voyeurism, power and the consumption of images – the irony was that the audience were becoming more interested in taking part, straightforwardly devouring the scenes placed before them. There is a built-in risk to performance complex enough to demand that the audience construct its own meaning, which Shunt's work self-consciously sets out to do: there must be enough remaining clues to offer some sense of being on the right track; the detective work required to piece experience together into meaning needs to be rewarded along the way. Here, the sense of mystery never resolves, and Shunt has cultivated an audience disinterested in anything but experience itself.

Beccy Smith

The Experiential Response

I'm given a key, no explanation, no instructions. Walking, stumbling through dank archways, why do these other people overtaking us seem to know where they are going? What's in those dark corners? Stumble on towards the light and sound into a bar. Are we there yet? Has it started yet? People playing pool. Junk shop sofas. Drink a much-needed whisky (medicinal, am cold and sniffling). What now? Through a door, lockers, oh, the key... a sparkly pink clown's hat, a name, a set of instructions. Another corridor, a room full of people, a room with a view. Not windows but live film sets; pig masks, a crooning cabaret artist, a ringing telephone. I obey instructions and leave; Beccy stays behind. A bedsit – teak tat, a mattress on the floor, a fridge, cheesy cheddars, our host a cringey bloke. We're all sitting nervously, we're left alone, the lights go out. Are we all 'real' audience members? Who'll pick up the ringing phone? Heavy footsteps above, crashing and banging, cries and screams; rape, murder or an S&M scene? Ushered out – who's making the decisions here? Ah, an usherette...

Into a cinema but oh my God, what we're seeing is a split-screen version of where we've just been. This whole thing is so Hitchcock, so Rear Window – but it would be, wouldn't it? Credits roll, new people come in. There's a bin bag on its own in the centre – very Gavin Turk. Humiliation – a woman orders a man to undress; he puts on a sailor suit. Glimpses of a trapeze artist swinging by on the other side of the divide. I wriggle on my seat, it's all a bit squirmy. Led out by the usherette, handed a torch, I stumble on with the herd. Now where? Into my own ripped-and-torn past, '70s squats – enormous places with cavernous low-lit rooms full of (it's all here) mattresses, screwed-up tissues, lumps of plastic bottles, some sort of scrunched-up bubble-wrap stuff, a piano that's seen better days, a few chairs. We shine torches around; objects are highlighted, framed by the light, given the Duchamp treatment, transposed into sculpture. Two women who look heavily pregnant smoking fags, swaying dangerously, staring us out, crawling on the floor. Am I having fun? I think I'm having fun. All too soon the party's over. Thank you and Good Night.

Dorothy Max Prior