Street Theatre in the UK is currently undergoing a significant makeover. In the 80s and early 90s you could have been forgiven for thinking nothing much was happening but now it is gradually moving into centre stage. One of the pioneers in this sea-change of opinion is the Stockton International Riverside Festival, which recently celebrated its 16th year. I corresponded with director Frank Wilson to find out more...

What was the initial inspiration behind your decision to put on an international festival in Stockton-on-Tees?

This has to be a two-stage answer because the first two Riverside Festivals were not really international at all. My initial impetus was simply to do something outdoors – I had taken over the management of Stockton's arts centre and realised during my first summer there (in 1987) that it was a thankless task attracting people into the arts centre in warm weather because the studio theatre didn't have an adequate ventilation system. (Actually I found out years later that it did, but our theatre technician had forgotten how to operate it!)

So in summer 1988 it seemed logical to take an arts programme outside the building. At the time I knew next to nothing about street theatre, but built a 48 hour programme around a community arts project (floating a symbolic swan on the then heavily polluted river Tees) and a British new circus company with their own tent. The success of the event exceeded all expectations, particularly Stockton Council's, who had confidently predicted that no one would be interested!

In 1989 most of the Festival budget went into a big show by Welfare State (who were coming to the end of their interest in 'spectacle' anyway), so the Festival didn't become international until 1990, by which time I had been inspired by things like Archaos in Edinburgh and first visits to the Tarrega (Spain) and Limburg (Holland) festivals to want to take the Stockton Festival in a definite direction.

What did you learn from the first festival?

I learnt that there was a much larger audience for free outdoor events than there was for ticketed studio performances in an arts centre! Also that the outdoor audience was a genuine cross-section of society including many people who, for a variety of social, cultural and economic reasons, were not consumers of the 'arts' in 'arts' buildings. Also that, contrary to stereotyping, this was an audience well able to recognise and appreciate quality and with a lively curiosity about new experiences. Eavesdropping on a range of responses to IOU's Journey of the Tree Man, a show as surreal and obtuse as anything I could hope to put on at the arts centre, convinced me of that.

Stockton is well-known for presenting large-scale European shows. Were they there at the beginning? If not, when was the first time you put on such work and what was it?

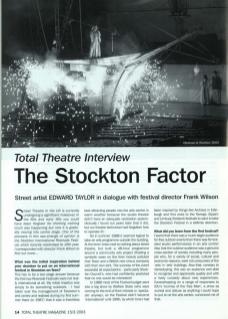

The first large-scale European company we presented was Compagnie Malabar in 1990. They did Voyage des Aquareves as a daytime show and Face à Face as the Festival finale. We had a crowd of about 4000 for the latter and, of course, the show is quite visceral – acrobatic stilt work, Mad Max motorbikes, rock music and lots of pyro. At the end the audience literally erupted with delight – I don't think a promoter or curator of work could fail to be excited by such a positive reaction.

Ideally it would be great if there was one defining moment when you knew that the festival would work in Stockton. So was there one or has it been a gradual process of winning the town over? Or were the crowds always with you and it was a case of convincing the funders?

Probably Malabar's Face à Face was THE moment – although I have to say the public was enthusiastic from the start. You have to remember that in the late 80s the North-East was suffering from the worst effects of Thatcherism – unemployment was at record levels and the retail sector was on its knees. The Festival was a breath of good cheer in difficult times. To give credit to Stockton Council, they very quickly revised their own views and by 1990 had already become the Festival's main funder.

The Festival budget grew very rapidly in the early to mid-1990s because of the Council's support and the cultural dimension of various economic regeneration strategies – Urban Development Corporation, City Challenge, European Regional Development Fund, etc. By 1992 Stockton had an enormous international street arts festival which had no equivalent anywhere else in the UK. Ironically, the only 'funders' who had yet to be convinced were in the formal arts funding sector.

Despite the size of the festival and the fact that you put on large prestigious groups, the national press coverage has been very sparse. Is this a London thing? Or do you think that street theatre still has work to do in convincing critics that it isn't just a bunch of jugglers and mime statues? Or do you think that the critics should do a bit of research too?

Yes to all the above. Stockton suffers particularly because it is not a destination where journalists fancy spending a few days. Also, as an August festival, we lose out every time to the Gadarene rush to Edinburgh. There is certainly a 'big city' attitude in Britain that nothing culturally significant could possibly happen in a town the size of Stockton – which is obviously not replicated in Europe (Aurillac, Tarrega, Terschelling, etc). The wider context is definitely that, whereas ACE is now a committed supporter of street arts, the media is the last bastion of wholesale scepticism about the work in this country. There are a few exceptions but there is a definite need to make the case that street arts is a more significant cultural phenomenon than sideshows for shoppers. Again, this is an argument that was accepted decades ago in countries like France and Holland.

We often hear British Street Theatre unfavourably compared to French, Spanish and other European groups. Is this comparison fair? Are there differences? Or does it depend on each individual show?

Thanks for saving the best till last! In brief, I think 'British Street Theatre' is progressing positively at the moment, unlike, say, Spanish street theatre, which is in the doldrums compared to 10-15 years ago. I think that improved funding opportunities for UK companies are definitely part of the reason that more diverse and ambitious work is being produced. But money is never the whole story, although listening to disgruntled artists at conferences you would think that it was. I know French companies who take enormous financial risks to make the work they are committed to. I also know when Biuro Podróży made Carmen Funèbre – an extraordinary show – they had no funding at all.

There are distinctive elements to 'British street theatre’, as there are to French, Spanish, Australian, and the rest. I think this is a natural product of individual historical, cultural and social experiences, and is to be welcomed as nobody wants a homogenised world street theatre. I'm amazed, for example, at how much more sophisticated our concept of multi-cultural work seems to be compared with much of Europe's – where you still see shows 'researched in Soweto', for example, which look more like old-fashioned 19th Century cultural expropriation. On the other hand, I do wish that we had a more robust tradition of actor's training in this country – one which properly equipped people for street performance. Many promising British shows are still let down by hopelessly ‘hammy' acting.

The Stockton International Festival website is at www.sirf.co.uk