Dancing in a cold, cavernous, four-storey, Victorian pottery factory is not for the faint-hearted. From January to April of this year, Punchdrunk Theatrical Experiences moved in to Offley Works in South London, to create The Firebird Ball – a large-scale performance/installation based around Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and Stravinsky's Firebird ballet.

Punchdrunk was formed in 2000 by a collaborative team led by artistic director Felix Barrett to produce work that aims to allow audiences to re-encounter childlike excitement and anticipation of exploring the unknown. Masked audiences are given the freedom to roam entire buildings and soak up the atmosphere of magical yet fleeting worlds.

Offley Works was not one of the architecturally grand spaces we'd been chasing (original sites had included the former Lloyds Bank headquarters in the City) – but it was highly atmospheric. The first day on site, Felix sent the performers individually into the space. Scattered on each of the floors, in corners and pinned on walls were improvisation tasks (‘respond to the rhythms of the space') and triggers ('who's hiding in the corner?') to stimulate performers' responses. I remember Lizzie Barker (Firebird) spending ages in the basement because she ‘loved that space'.

The performers had very instinctive responses to areas and it was important as directors that Felix and I trusted their appetite for the environment.

I felt daunted. Despite having found the site with Felix, I couldn't quite get my head around how the show would fill this epic building. What if the audience lost themselves in the matrix of the basement? Navigating the audience around the space, suggesting without telling, teasing without taking was one of the main choreographic and performative challenges of the project. Small moments of touch, a gesture, a look, a stillness, became triggers to direct audience focus.

In The Firebird Ball, each character followed his or her narrative journey – known as the 'loop’ – organised by its location and content. This was storyboarded in advance of rehearsals to save time and to prevent the space overwhelming the devising process. Each loop lasted 52 minutes and was performed three times in one evening.

The audience could – should they wish – latch on to the loop and use it as a tool for navigation.

The loop format develops a structural concept, which infuses the multi-dimensions of theatre with a cinematic sensibility so the audience becomes an invisible witness on a film set. The implications for 'staging' a play within this format (albeit a play without words) are significant as all characters are present at all times. There's nowhere to hide. This results in the need for a density of theatrical and choreographic material. Some audiences found the multiple stories confusing, desperate for that Hollywood-style singular narrative fix, whilst others delighted in working it out or following a whim.

Initially, Felix and I worked for three weeks with the performers at the Jerwood Space whilst the design team began the installation work. Felix had designed the four floors of the space, together with the entrance and exit routes, drawing on images and environments from both the fairytale and the play to include a magical forest, a desecrated church and a blown-up living room. The design was fundamental in inspiring, framing and illuminating the choreography and the narrative. In the main, my responsibility was to work with the cast, but Felix would move between rehearsals and site, facilitating the devising process and feeding the aesthetic relationship between body and space. Our collaborative process in the main was/is very fluid – I share in Felix's vision about theatre and the nature of theatrical experience. Intimacies of distance and experience lie at heart of our ambitious, big picture sensibility.

We battled over use of music. I found it difficult, as a choreographer, to completely relinquish ownership over this element of the work. Ultimately, I trusted Felix's talent (and collaborator Stephen Dobbie) to hear the show as a sound design for site as opposed to a score for the stage.

Studio time is a core part of our process as it is during this period that we devise the more physically demanding elements of the dance/movement theatre language before transposing it to the site. I find transposition a handy choreographic tool in site work as movement can often gain from the limitations imposed by the physical conditions of its environment. As an example: the fight/death scene between Tybalt, Mercutio, Romeo and Paris was a challenge. The architecture of the fight room' was imposing with a low ceiling and four centralised concrete pillars. It possessed a kind of hostility essential for this scene. When reworking the pre-choreographed material, we found that the real risk in the contact-based partner work had to be modified to compensate for the hostile features of the room (cold, concrete floor, sharp edges). It was difficult to impose movement onto this space. The most edgy material emerged.

Small moments of touch, a gesture, a look, a stillness, became triggers to direct audience focus when the dancers went with its inherent physicality, climbing up pillars and diving off ledges.

One of the pleasures of the project was noticing ways in which the site and design continually informed our (performers and directors) choreographic and directorial instincts and made us engage with the present. Discovering the tricks and surprises of the site was an infinitely evolving process. During the fifth show, I walked around a corner and was surprised to see Jami Quarrell hanging upside down in a doorway, blocking the audience's entrance. This developed over the course of the run into a witty choreographic game of 'should I stay or should I go?' between performer and audience.

A naturalistic scene between Lady Capulet and Tybalt devised in the studio became something much more visceral after I'd visited Lady C's actual, intimate and very red dining room on-site. This space was filmic in its form (windows and doors offered possibilities for multiple and simultaneous framings) and so rich in character that it seemed wasteful to use it simply as a context for narrative. The dining room desired a danced duet. Sarah Dowling (Lady C) and Jami (Tybalt) responded to the space by choreographing their kissing, holding, falling, balancing dance within the physical boundaries of the window ledge – offering an 'on the edge’ metaphor for their relationship. Some people peeped through the windows whilst others used their masks to get up close – intimacy at a distance.

Lady Capulet's solo also grew organically from that space. In the studio, Sarah had been working on opposing tensions within the body to try and find the abstracted, dance essence of her character. The dining room space seemed to illuminate the angularity and tension we'd been exploring in the body and her solo developed as a three-way dialogue between dancer, choreographer and space.

The weather was definitely against us.

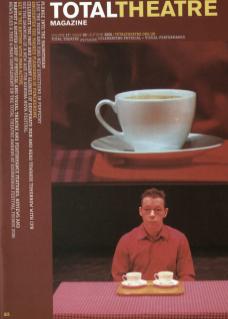

The site was freezing. I remember laughing as it started to snow – in March – as I was driving to the site. During rehearsals people would spend as long as they could bear it in their spaces and then hide out in the warmth with a cup of tea. At times, I felt more like a shop supervisor than choreographer, calling time on cigarette breaks and persuading people to do just another half an hour.

Never again.

Not in the cold

Not until next time...

Maxine Doyle is a choreographer and a director of Punchdrunk Theatrical Experiences. She teaches Physical Theatre at St Mary's University, Twickenham. The Firebird Ball was produced by Punchdrunk in association with Creative London and The Big Chill and funded by Arts Council England. For further information on the company history and future projects, see www.punchdrunk.org.uk