Two shows, two cities. The first in London, the second a week later in Paris. Fragile reasons for comparison: video and music; both made by artists of thirty-five years'-plus experience; both about death. One was People Show's The Obituary Show (Riverside Studios, London). The other the Peter Sellars / Bill Viola production of Wagner's Tristan and Isolde at the Opera Bastille, Paris,

What intrigues here is the sheer scale of difference. I saw them within a week of each other, yet the distance between these two performances is to be measured in light years. They occupy totally separate universes, positioned on opposite ends of the performance spectrum. The Paris show was taut, spare, emotional. London's People Show, busy, quirky and sentimental. To think about Tristan and the People Show at the same time is to experience the theatre equivalent of seismic jolt. This is not about size or resources – it is a perfect example of how performance divides into two incompatible and opposing creative practices. The driven pursuit of minimalist aesthetic on the one hand, and on the other, the bricoleur – the random rather than organised collection of theatrical scraps and fragments.

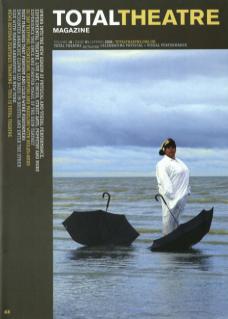

Peter Sellars directs Tristan and Isolde with what can only be described as 'absolutist minimalism'. Once, and once only, a man breaks into a run – to go off-stage. The performers stand and sing, or stand silently, illuminated by square blocks of dim white light. All the movement and colour happen in the four-hour video projection of Bill Viola's work. A huge screen is filled with images of water, trees, a naked man and woman, the sea, fire. The process is meticulous, deliberate. A tiny dot gets closer and closer till it comes into focus – it is a woman on a beach, a ship on the horizon. In the final scene, circus artist Sarah Steben floats in a digital water world, her white dress billowing and curling as she ascends. It accompanies the last moments of the music, where the lovers ‘are drawn up in peace' to a place 'beyond light and darkness, beginning and end' (Viola's programme notes). It is a stunning visual evocation of the mystical union of man and woman.

In The Obituary Show, People Show assemble a car-boot sale array of props and paraphernalia to create an office of indeterminate period, a room with a piano and a café. They meander from scene to scene looking for information about an unknown musician who has just died. They play some musical instruments, they speak long monologues in an increasingly manic manner. Minimal they are not. Everything on stage, from the typewriter to the filing cabinet, looks (and probably is) like some found object that has been left there by accident or mistake. The video is screened on a small television set that seems like an item from a house clearance sale that nobody wants. The Obituary Show is the theatre equivalent of an English allotment – odd bits of things rearranged to make them fit for a completely different purpose. It's as if nothing, including the show itself, is really sure why it is there and what it is meant to be doing. This People Show is not anarchy (as their flyer claims). Rather it is a gentler, cruder kind of control, a 'rough' theatre, vaudeville, the 'nothing too deep' show. People Show know this and are quite happy to deliver.