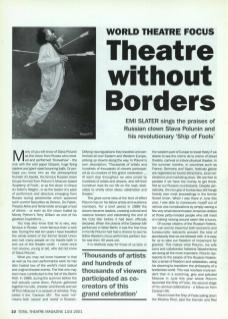

Many of you will know of Slava Polunin as the clown from Russia who created and performed Snowshow – the one with the wild paper blizzard, huge flying spiders and giant-sized bouncing balls. Or perhaps you know him as the philosophical founder of Litsedei, the famous Russian clown troupe formed from Polunin's Moscow-based ‘Academy of Fools', or as the clown in Cirque du Soleil's Alegria, or as the leader of a pack of performers and directors emerging from Russia during perestroika which spawned such current favourites as Derevo, Do-Fabrik, Theatre Akhe and Terramobile amongst a host of others – or even as the clown hailed by Monty Python's Terry Gilliam as one of his greatest inspirations...

You may also know that he is very, very famous in Russia – more famous than a rock star. During the last ten years I have travelled the whole extent of the former Soviet Union and met many people on my travels both in and out of the theatre world – I never once met anyone, young or old, who did not know of Slava Polunin.

What you may not know however is that as well as his own performance work he has also hosted two of the world's most radical and original theatre events. The first one may even have contributed to the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1989, during the summer before the wall actually came down, Polunin gathered together his wife, children and friends and set off from Moscow in a caravan of vehicles. They called it the ‘Caravan Mir'. The word 'mir' means both 'peace’ and ‘world' in Russian.

Defying visa regulations they travelled and performed all over Eastern and Western Europe, picking up clowns along the way. In Polunin's own description: 'Thousands of artists and hundreds of thousands of viewers participated as co-creators of this grand celebration... At each stop throughout we were joined by hundreds of artists and viewers, who left their humdrum lives for our life on the road, dedicated to wholly other ideas: celebration and theatre.'

This gives some idea of the kind of effect Polunin has on his fellow artists and audience members. For a brief period in 1989 the clowns became leaders, crossing cultural and national borders and celebrating the end of the Cold War before it had been officially declared. When the clowns of the Caravan Mir performed in West Berlin it was the first time in his life Polunin had had a chance to see his fellow Western circus performers perform live: he was then 40 years old.

It is relatively easy for those of us born in the western part of Europe to travel freely if we desire to see the crème de la crème of street theatre, carnival or indoor physical theatre. In the summer months, in countries such as France, Germany and Spain, festivals galore are organised as tourist attractions, local celebrations and marketing ploys. We are free to partake if we have the money to get there. Not so our Russian counterparts. Despite perestroika, the iron grip of bureaucracy still hangs heavily over most proceedings in the former Soviet Union. When I was there in June this year, I was able to manoeuvre myself out of various visa complications by simply waving a few very small denomination American dollars at those petty-minded people who still insist on making moving around seem like a luxury.

Of course citizens of the Russian Federation can and do travel but both economic and bureaucratic restraints prevent the kind of spontaneity that we are blessed with. It is easy for us to take our freedom of movement for granted. This makes what Polunin, his wife Lena and collaborator Natasha Tabachnikova are doing all the more important. Polunin represents to the people of the Russian Federation a sense of freedom and celebration, using his clowning to transform the philosophy of a borderless world. This was nowhere more evident than in a scorching, grey and polluted Moscow in June this year where Polunin launched the Ship of Fools, the second stage of his carnival celebrations – a follow-on from Caravan Mir.

Polunin took the Ship of Fools sailing down the Moskva River, past the Kremlin and Red Square, launching the largest street theatre festival ever held in Russia. The huge multinational event marked the close of Theatre Olympics 2001, described by Vladimir Putin as 'an exchange of ideas which defines the future of scenic art'. The concept behind the festival, which ran from April to June 2001, was no less ambitious: ‘The Moscow Theatre Olympics will be held at the turn of the two centuries and the two millennia. The Olympics will become the demonstration of results of theatre development in the 20th century in a broad variety of forms: from experiments of avant-garde to folk street shows. By showing the crowning achievements of the world stage; by showing the modern theatre at the Olympic heights, we are helping the national theatre – first and foremost the young generation of theatre practitioners who will take hold of the 21st century stage – to measure their art against the world theatrical culture.' A fitting aim for the capital city of the nation which laid the foundations for so much of the legacy we physical theatre practitioners have inherited today.

The festival was divided into blocks: foreign theatre companies, Russian theatre companies, experimental theatre companies (including Forced Entertainment, Eugenio Barba, etc) and the street theatre programme headed by Polunin. His enthusiasm and passion to bring to his fellow Muscovites the best of what he describes as ‘theatre without borders' resulted in a festival which included solo performers and companies from all over Europe – east and west – and beyond. An enormous number and range of performers were present – including clown Leo Bassi, Strange Fruit (Australia), Akhe Group (Russia), Perekatipole (Estonia), Teatr Biuro Podróży (Poland), Els Comediants (Spain), Red Elvises (USA), the UK's Natural Theatre – plus numerous design installations, carnival processions from all over the world, workshops, and music groups.

The festivities were focused around the gardens of one of Moscow's many very beautiful state theatres, the Hermitage. Other companies, such as the Netherlands' Dogtroep, were programmed to perform in the spectacular location of Revolution Square, which opens out into Red Square. Natural Theatre Company, frustrated at being restricted to the Hermitage Gardens, broke out and took their Red People walkabout characters into Red Square where, contrary to expectations, a young policeman guarding Lenin's Mausoleum asked to be photographed with them rather than arresting them. Surrounded by a stunning fire installation by French company Carabosse, numerous other companies performed throughout the evening: notably Alarm Theatre from Russia/Germany, and the French company Malabar who stormed the gardens with pyrotechnics that would have made British safety officers have a cardiac arrest.

A sense of joy and excitement and fearlessness is something Polunin and his team carry everywhere. They defy bureaucratic gravity by organising events which make a mockery of any administrative problems we in the west may complain about. The new-found freedom felt by most Muscovites in their lives is feared to be temporary. Most of the people who live in that vast city with its history of theatre and revolution and literature and art feel their lives are still lived at the edge of a precipice. Polunin and Tabachnikova's Ship of Fools is a festival of genuine celebration – something we need more of. We must put an end to the glorified marketing machines or expanded tourist attractions so many festivals have become: theatre is for real life, the food of our souls.

As Polunin himself puts it: ‘The state of celebration is a special one, elevating the human condition. When we put on our beautiful costume, arrange our hair, lift our eyes, and polish our shoes, we transform ourselves into a celebratory mode and become actors in the process. We do so in order to “create” our image and participate in an event that is different from the everyday, grey existence in which we are cogs in a huge machine.' Long may the Ship of Fools keep sailing...

Emi Slater is artistic director of Perpetual Motion Theatre, who have recently returned from Eastern Europe. Their new show Perfect is currently being previewed and will tour in 2002. See www.perpetualmotion.org.uk