‘Anything can be a puppet,' said Douglas O'Connell, speaking at the Total Theatre Network Critical Practice Debate on puppetry and animated theatre. And going by the visions 2000 Festival of International Animated Theatre, the objects or body parts that the artful animator can transform are limitless: plasticine models, faceless dolls, mechanical automatons, even a belly button.

Most theatre anthropologists consider object animation to be amongst the earliest means of artistic expression. Participants at the debate mentioned the role of the totemic object, mask or puppet in humanity's earliest rituals, and yet puppetry and object manipulation are still at the heart of the creative impulse in the 21st century. From mud pies to finger rhymes, from peek-a-boo behind the curtains to Action Man and Barbie – our childhoods are defined by our animation of the environment we find ourselves in. The theatre-maker shares with the child this desire to make sense of the world – to use whatever is available to represent and transform, to act and re-act.

The visions 2000 Festival of International Animated Theatre, held throughout October at various venues in Brighton and nationwide, was an opportunity to see how the animators of today are developing the art form. There was something for everyone – from Theatre-rites’ Sleep Tight (aimed at the under fives), to a strictly adults-only cabaret from Moving Hands, featuring Music Hall artiste Miss Ida Barr playing Aunty to a rather naughty puppet who bares her breasts and rolls a spliff when Aunty nips off to the bar for a gin. This show is a good example of something that is both old and new – the company are taking puppetry to new audiences in comedy clubs, but the notion of the naughty doll with a mind of its own is a trick discovered early by every young child, and exploited extensively by ventriloquists.

That puppets can be more human than humans themselves is a notion dear to French company Flash Marionettes. 'When a man and a marionette face each other on a tightrope wire, the public dread the fall of the creature made of wood and foam more than that of the man,' read the programme notes for their show Flash Circus. Perhaps more to the point, we can allow ourselves emotions expressed through the medium of a marionette that we would otherwise keep hidden – hence the success of the use of puppetry by psychologists and therapists when dealing with survivors of trauma and abuse.

A rather different form of animated theatre was brought to the festival by Indefinite Articles. Dust is a collaboration between Steve Tiplady and Spanish artist/director Joan Baixes. There is not a puppet in sight, but plenty of objects to be animated. Another interesting piece was At Home by Wireframe – an animated environment for an audience of one. The company prove that virtual reality is about far more than a computer screen. With calico, plasticine, simple lighting and an ambient soundtrack, the unseen artists create a sealed-off alternative world that allows the participant fifteen minutes to work, rest or play. Everyone that I have spoken to said it was the best fifteen minutes they've spent in a theatre for a long time. And, of course, with an audience capacity of one you achieve a sellout at every performance.

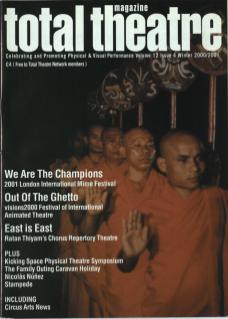

Total Theatre Network's Critical Practice 9, held as part of visions 2000, was an opportunity for practitioners to look at the ways in which puppetry and animated theatre are pushing the boundaries into new ways of working. For, according to Mervyn Millar of Wireframe, puppetry needs to ‘get out of the ghetto' to survive. We looked at ways in which challenges were made to audiences' expectations of the form. Festival director Linda Lewis pointed out that puppetry in this country is too often seen as being just for children rather than of universal appeal and that there is still a lot of work to be done to bring the form to new audiences.

Achieving a balance between respect for the tradition and reaching for the new was a theme that emerged soon in the discussion. There was an awareness that what goes round comes round – animated theatre is one of the oldest forms and has never existed in isolation from other arts disciplines. From the earliest days, the integration of different modes of expression in what we now refer to as multi-discipline art practice has been a key element of theatre: mask, mime, poetry and puppetry have sat side by side throughout history. Sometimes one element gets put aside for a while, to re-emerge as a 'new collaboration’ in another era. In my introduction to the session, I spoke of the work of early 20th century visual artists who had integrated puppets or automata into their work, such as Alfred Jarry's Ubu Roi and Marinetti's Pouppées Électriques. Within dance and theatre performance, the Russian director Meyerhold slotted vigorously trained performers into a jamboree of constructions to create an automated environment, and the director of Bauhaus Stage, Oscar Schlemmer, explored the object qualities of performers, coming at one point in his career close to Gordon-Craig's belief that actors were a hindrance to theatre and could be replaced by 'Uber-Marionettes'.

We can allow ourselves emotions expressed through the medium of a marionette that we would otherwise keep hidden.

The freedom for the theatre-maker in using objects rather than performers was something commented on by a number of practitioners. The idea that anything can be represented – that there are no limits to the imagination for the visualiser – was seen as the reason why many people chose puppetry or animation as their medium. To those of us who struggle with the material world, the counter argument is that there is no reason why the physical body cannot express any idea – it ultimately comes down to finding a means of expression that suits the artist (there being no superiority or inferiority in any means of expression).

Outside of the realms of stage theatre and into the wider world, Douglas O'Connell spoke of the value of using objects in community projects as a way to help kids grapple with the challenges of discovering and celebrating their personal identity, feeling that they help them to feel less self-conscious. An American with an impressive track record with Steppenwolf and Emergency Exit Arts, Douglas is now working in Brighton with GLAM (Gay and Lesbian Arts and Media) developing projects that integrate visual theatre within a community arts setting. He spoke of the influence of companies such as Bread and Puppet Theatre and showed a video of his Gallery 37 project for the Greenwich and Docklands Festival. Douglas expressed his preference for working without spoken text.

There was heated discussion, as always in any debate on visual or physical forms of theatre, on the place of the word. As a writer, Sean Prendegard felt that there were some occasions when words were the only way that something could be expressed. This was hotly disputed by many of those present, who felt that there wasn't anything that couldn't be expressed in visual imagery. On the subject of poetry, Terry Lee from Green Ginger said that there wasn't a lot of room for poetry in his work – which he refers to as 'micro theatre' rather than puppetry. Green Ginger are a company that cut their teeth in street performance. MTV-style fast edits and short sharp shocks are the stuff of this theatre, which aims to sacrifice a few sacred cows along the way. Green Ginger, although a highly visual company, do rely heavily on spoken text as an integral part of the narrative of their latest work, Bambi – The Wilderness Years.

Sean Myatt and Felicia Negomireanu from Theatre Insomnia use dialogue and storytelling in their latest work, The Golden Bridge, which aims to preserve rather than uproot the traditions by using stillness and the gentle magic of the fairy tale to tell universal truths. ‘We are no longer a culture that understands symbols,’ Myatt said – which I interpreted to mean that though surrounded by symbols we have reached a cultural overload where we have lost the shared language of universal symbolism. Is this really so, or are the archetypes and images of the contemporary world fragmented but still understood? Are we, like the occupants of Plato's Cave, deluding ourselves that shadows are reality? Or did Plato get it wrong – perhaps there is nothing more real than the shadow itself. The notion of a shared language emerged from the discussion as crucial to visual forms of theatre; artists can come from many different starting points but collaboration relies upon a common understanding – a belief perhaps that reality is not a solid mass of fixed forms but a fluid flow of veiled illusions.

Critical Practice 9 has been recorded by the Arts Council of England archives and can be heard as a webcast on www.artsonline.com until the end of February 2001.