Youth work, according to fecund theatre, is no longer about exploring local history in order to present a plot-driven narrative piece of traditional theatre to the local community. The idea is to provide those involved with an ‘intense experience’, one that they will never forget.

Commissioned by Southern Arts Board in conjunction with Spring Gardens Arts Centre (where fecund are the company in residence), the group's brief was to develop a piece of theatre that celebrated the centenary of cinema using their unique style of visual, physical and multimedia performance work. Working with 18-25 year-olds, the company initially rehearsed one evening a week up to the Easter holidays, after which the work became more intensive.

John Keates, writer, director and co-founder of the company, believes that his role in a youth project is about providing those involved with an opportunity to experience his company's full working methodology. This meant that for the two weeks prior to the production, the whole group stayed together under one roof – living, sleeping, eating and breathing the work. It meant that the performers had to take on board John's deconstructive and political philosophies concerning theatre practice, which lie not in issue-based work but ‘in placing art, energy and style into the theatre space’.

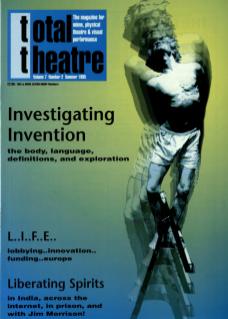

The original brief soon became lost under the rubble of deconstruction, and the ‘celebration’ of cinema soon turned to analysis of the star system, the public's perception of ‘stars’ and a focus on the stars' mythology and destruction until, having watched the Oliver Stone film, The Doors, the figure of Jim Morrison was decided upon.

The group began to explore the ‘living’, contemporary myth of Morrison. Such exploration involved rehearsals and video shoots until four in the morning, drinking Southern Comfort and Jack Daniels in an attempt to absorb and understand the man behind the myth. Getting a group of impressionable performers drunk is perhaps not everyone's idea of ‘safe’ youth work and John admitted that some of the original participants did drop out. His reasons for working as he would with the professionals in his company, however, remained strong: ‘everything they do from now on will be easy. We were not interested in creating a piece of documentary theatre. Our work is about hardcore issues – depression, blackness and destructive intelligence.’

It was important for John that the performers were able to deal with pressure and create under stress – intellectually, emotionally and physically – any anger or breakdowns were then chanelled into the production.

His actors earned the right to be on the stage, and what was sometimes incorrectly seen as arrogance in the performers' work, was actually a belief and conviction in the end product.

In many ways, John saw the figure of Jim Morrison as a licence to work in this manner with the performers. As he suggested, some of fecund's earlier work was criticised for using hardcore imagery, but an exploration of a man such as Morrison involved a distillation of the facts and the subsequent transcendence in the performers providing them with the freedom to push the boundaries of their previous performance experiences. And the end product?

The form and execution were unmistakably fecund. John had succeeded in drawing out intense and demanding roles for the actors. All of them performed exceptionally well with the result that one's idea of youth theatre as being stale and uninteresting was no longer valid.

It is important that practitioners such as John Keates do not compromise their artistic integrity when working with youth groups. By operating in this manner all involved – audience and spectators alike – learn and participate in a fulfilling experience.