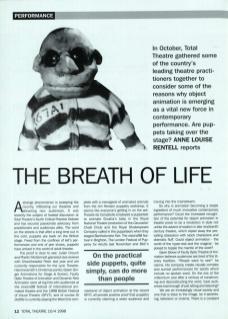

A strange phenomenon is sweeping the country, infiltrating our theatres and attracting new audiences. It was recently the subject of heated discussion at Total Theatre's fourth Critical Practice Debate and has secured passionate advocacy from practitioners and audiences alike. The word on the streets is that after a long time out in the cold, puppets are back on the British stage. Freed from the confines of kid's performances and end of pier shows, puppets have arrived in the world of adult theatre.

The proof is clear to see: Julian Crouch and Phelim McDermott garnered rave reviews with Shockheaded Peter last year and are currently responsible for the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith's Christmas panto; Green Ginger, Animations for Stage & Screen, Faulty Optic Theatre of Animation, and Dynamic New Animation were all big hits with audiences at the visions98 festival of international animated theatre, and the 1998 British Festival of Visual Theatre (BFVT); and of course Dr Dolittle is currently playing the West End complete with a menagerie of animated animals from the Jim Henson puppetry workshop. It seems like everyone's getting in on the act: Theatre de Complicite employed a puppeteer to animate Grusha's baby in the Royal National Theatre production of The Caucasian Chalk Circle and the Royal Shakespeare Company called in the puppeteers when they staged Bartholomew Fair. The visions98 festival in Brighton, The London Festival of Puppetry for Adults last November, and BAC's weekend of object animation at the recent BFVT, all provide positive proof that puppetry is currently claiming a wider audience and moving into the mainstream.

So why is animation becoming a staple ingredient of much innovative contemporary performance? Could the increased recognition of the potential for object animation in theatre prove to be a revolution in style not unlike the advent of realism in late nineteenth century theatre, which wiped away the prevailing obsession with stock characters and dramatic fluff. Could object animation – the world of the hyper-real and the magical – be poised to topple the mantle of the word?

Gavin Glover of Faulty Optic Theatre of Animation believes audiences are tired of the literary tradition. ‘People want to see!’ He claims. His company create visually complex and surreal performances for adults which include no spoken word. On the eve of the millennium and after a century of constructing and deconstructing the word, have audiences had enough of just sitting and listening?

We are an increasingly visual society and one that is slave to the image, be it advertising, television or cinema. There is a constant search for the ultimate in visual stimulation and contemporary theatre is buying into this. This is evident in the fact that auditoriums are full to capacity for Cirque du Soleil tours and musical extravaganzas like The Phantom of the Opera. Penny Bernand, Artistic Director of the London-based company Theatre-rites, believes that audiences have a desire to be transported in the theatre into new worlds: ‘Audiences don't want to go to the theatre to have their everyday life reflected back at them.’ Puppets can give the illusion of reality without themselves being real, thus they can potentially provide an instant theatricality to a stage production. Green Ginger prove this point beautifully in their currently touring production Slaphead – the puppets are life-size and to all intent and purpose 'real', but the comic-book nature of the visual style removes the theatrical representation from the everyday to present a world of super-human possibility.

On the practical side puppets, quite simply, can do more than people. Like film and computer animation, puppetry makes the impossible possible. In Green Ginger's Slaphead, heads explode and tongues are ripped-out live before an audience in anarchic disregard for the impossible. In the show Tunnel Vision, Faulty Optic has created a large and complex world in miniature, put it into a small space, and invited the audience to view it through live video projection. This method, ingenious in its simplicity, surmounts all kinds of normal practical limitations. Faulty Optic is able to focus their audience on the detail in their work, thus acting like cinema auteurs, showing the audience what they want them to see.

That said, it must be remembered that puppetry is one of the oldest forms of performance and surely it satisfies more than a desire for visual stimulus or practicality? There is something intrinsically precious about how an animated object is able to make an audience see and feel. In this sense, puppetry is a kind of magic realism. If we go back to the traditional story of Pinocchio and his master Gepetto, we can recall how an inanimate object was brought to life through the sheer force of belief and love. It is this kind of magic that invests the art and skill of puppetry with poetry.

Sue Buckmaster, also of Theatre-rites, believes that the relationship between an object and its animator is one that everyone can relate to from their childhood. A child's relationship with a favourite toy signifies an emotional investment without which the toy would be meaningless. A similar dynamic between animator and object exists when puppetry is performed on stage. For instance, in Tunnel Vision, the puppeteers’ presence is both a sinister force and a comfort in an imagined world of solitude and darkness. Sinister because they are responsible for the puppet's existence in that world, and comforting because through their presence the audience is reassured that this existence is only imaginary and therefore temporary. Without the puppeteer, the puppets are not only free of this world, they cease to exist within it entirely.

For Sue Buckmaster, puppets have a unique power because rather than simply imitating life, they have the capacity to transform it alchemically. Puppetry can take the familiar and transform it, before an audience's eyes, into something new. This power is in the control of the animator, but also relies on the viewer’s willingness to suspend their disbelief. Green Ginger achieve this effect in their unsavoury, even disturbing, work and Faulty Optic question their audience's view of the world by presenting them with an alienating vision that is far removed from the everyday.

Animation is still an elusive form that defies any absolute definition. According to Rachel Riggs of Dynamic New Animation, puppetry is situated somewhere between performance and visual art: ‘Its lack of definition is indicative of its positive capacity to devour every other art form and make it its own. It provides freedom, the joy of play and the possibility of constant imaginative invention.’

So it would appear that the future is bright for a stage which welcomes the visually inventive. If theatre is on a downward spiral, it's probably because it can't, and shouldn't, try to compete with film and television. Rather, theatre should recreate its capacity to be a world in itself. In this world the audience should meet the performance halfway and engage with it with the wonder of a child.