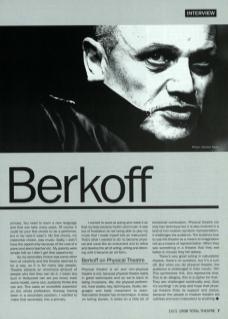

It was with some trepidation that I arrived at Steven Berkoff's impressive Docklands office. He does seem to cause unease in the public mind. Anecdotes I'd heard about him were vague and their provenance difficult to trace, but the general opinion seemed to be that Berkoff is not a nice man: a bullying egoist at best, a rabid lunatic at worst. And to make matters worse, he had recently been on the receiving end of a vicious savaging from the press after inadvertently breaking the Equity strike by providing a voice-over for a McDonald’s commercial. Berkoff's misdemeanour made front page news after fellow actors attacked him for accepting the lucrative offer and contravening Equity's dispute over proposed pay cuts in the advertising industry. I suspected that journalists would probably not list among the actor's favourite people at present.

Berkoff's office did little to allay my feeling of unease. In one corner of the large space is a desk, and folded against the wall is a full-size table tennis table. Mr Berkoff, his assistant informed me, plays a lot of table tennis in his office and also uses the space for rope-skipping. Photographs of Berkoff as Corialanus hang on all the available wall space. In the few moments before he arrived, I found myself wondering what kind of person could bear to be surrounded by so many imposing photographs of himself. I soon found out. In conversation Berkoff is exacting, focused, garrulous and slyly humorous. He is given to passionate hyperbole, piling adjectives on top of each other in an attempt to capture fully the depth of his feeling on a particular subject. And despite my role of inquisitor, Berkoff mostly regarded my questions as a leaping off point from which he would return time and again to favourite topics. For the record, despite my fears, I enjoyed my time talking to Steven Berkoff about Steven Berkoff.

Berkoff on Beginnings

I started when I was about 21. There was never a how: it was more a feeling, a kind of taste for, a chemical reaction to the idea of doing something a little bit creative. I think every young person wants to be creative in some way and so you look for outlets.

Theatre tends to be, to a certain extent, a secondary outlet of creativity. A primary outlet of creativity would be painting, music composition, singing. I think those are primary. You need to learn a new language and that can take many years. Of course it could be your first choice to be a performer, but in my case it wasn't. My first choice, my instinctive choice, was music. Sadly, I didn't have the opportunity because of the cost of a piano and piano teacher etc. My parents were simple folk so I didn't get that opportunity.

So my secondary choice was some other form of creativity and the theatre seemed to be a way, as it is for many lazy people. Theatre attracts an enormous amount of people who feel they can do it. I mean any bum in Hollywood can act you know, even some model, some slut, suddenly thinks she can act. This casts an incredible aspersion on the whole profession. Anyway, having been in a secondary position, I wanted to make that secondary into a primary.

I wanted to excel at acting and make it so that my body became rhythm and music. It was out of frustration at not being able to play my music that I made myself into an instrument. That's what I wanted to do: to become physical and vocal like an instrument and to refine and develop the art of acting, writing and directing until it became an artform.

Berkoff on Physical Theatre

Physical theatre is art and non-physical theatre is not, because physical theatre starts in great techniques and so we're back to being musicians. We, the physical performers, have scales, key, techniques, rituals, languages and body movement to learn. Naturalistic theatre has no technique. It relies on telling stories. It relies on a little bit of emotional combustion. Physical theatre not only has technique but it is also involved in a kind of non-realistic symbolic representation, it challenges the audience. The audience love to use the theatre as a means to imagination not as a means of representation. When they see something in a theatre that they see better in movies they fall asleep.

There's very good acting in naturalistic theatre, there's no question, but it's a turn off. But when you do physical theatre, the audience is challenged in their minds: 'Oh! This symbolises this, this represents that. This is an allegory, this is a cipher for that.’ They are challenged continually and, God, it's exciting! I do pray and hope that physical theatre finds its support and status, because the people in modern theatre are ruthless and even malevolent to anything outside their own limited range and they won't give it space. There is no notion of doing this kind of work, of even doing exercises in it. There are no exercises, classes, anything, really developing techniques of physical representation in any of these big theatres. They don't want it, they don't like it and they really can't deal with it. It's another language. Their language is the language of oppression. It's the language of sets, huge costumes, great revolving stages at huge expense, continuous blagging for money – really conventional.

Berkoff on Film

I don't actually work with any other directors except movie directors, who are appalling directors. They very rarely let you have your way and yet when they do the films are successful, because then they can tap out of me all sorts of wondrous tricks. In Beverly Hills Cop, the director told me to improvise and the film took £600 million. It was a big box office hit, a famous film and now a real cult movie. I could've capitalised on that, have become a big star like Hopkins, but I didn't. I came back to England! Still struggling, knocking on doors of shithole theatres asking 'Can I have a job?’ I must have been out of my mind! I was crazy. I turned down Blue Velvet. I turned down millions. I could have had success. Instead I crawled back to this hole. I must've been insane but I felt I needed to belong to a primary art and film is still a secondary art. My spirit cried out for primary art. I wanted to do Hamlet not fucking Beverly Hills Cop, so I came back to a one-man show, The Tell Tale Heart, at the Donmar – which was a very dynamic theatre then.

Berkoff on Good Theatre

I admire the one-man shows of George Dillon, a disciple of mine. He's gone in a little bit of an odd direction recently. When I first saw him he adapted my short stories for the stage. It was unbelievable what he did. I think through repetition he lost it a bit. He can't get work because he is over-skilled for second division theatre. It's unbelievable. He cannot get a fucking job because he's too skilled for simple-minded naturalistic theatre! That's why I think the establishment and its naturalistic theatre are cultural cannibals. They take the money, they beg for more, they're always wheedling and yet they shut out any germ of dangerous avant-garde innovators... So poor George, he can't get work.

I know that Theatre de Complicite kind of hustle around. They're good. They're very, very physically orientated but their acting isn't that great. That's why they often get people from the straight theatre to come in. My company's acting is first and foremost – the tops. It had to be to compete with the best straight acting: the Oliviers, the Albert Finneys, the O'Tooles or whatever. I'd done ten years of naturalistic theatre so I could give my craft the structure of physical theatre. The combination – POW! – blew up. And it blew up when I did my first piece. I wrote East and put it in the framework of physical theatre and it became a cult hit. Then it was very simple: pretend riding motorbikes and dancing. The eating scene was very realistic. Other things, including talking facing out front and very gestural acting were bold and confronted bourgeois taboos. It was very, very good.

DV8 are excellent physical dance. It's still more theatre than dance to me. I've seen some of the work of Guy Hartman. I saw him do Animal Farm. I was terribly impressed by him, very, very, very impressed. He did the whole show by himself, doing all the animals, you know. It was wonderful. He never works – he should be used.

Berkoff on Equity

You know that brouhaha I had about the commercial? Well, I needed the money. I wasn't even aware that there was a strike on. I didn't realise because I had been abroad. I did it because I'm a complete innocent. I don't work here, I'm not nourished here, I'm not fed by the establishment. So consequently I don't feed at their table... I don't get food from them anyway. Why should I strike for something I'm not even getting? This is the supreme irony. I generate my work myself from my own funds. I'm independent. I don't care for their awful business... I'm a performance artist. I create and nourish and make and people come to see my own things, my own plays. They see me do play after play, year after year. Not one year did I leave out and there's a kind of resentment that's in their blood: contaminated, poisoned by their own resentment.

They don't even realise that the ferocity of their response is really due to their being poisoned. They could have said: 'Look if the guy does his own work and has, over twenty five years, changed the face of theatre, then there must be some reason. Maybe he's desperate, maybe he needs money, maybe he has some terrible problem. Find out. Equity check him out.’ I would have said ‘I'm sorry. I didn't realise.’ I'd give half the money back to the fund. I would have done it but instead they go crawling to the papers. I could give you the names of 150 people who have done what I did. Yet Equity had the temerity, the barefaced cheek to say I was the only one. They wanted to Shylock me. It was a kind of a racist conspiracy.

It didn't matter though. The people who conjectured most were second-rate actors anyway. I was really disappointed. I thought the response might have featured some better actors!