Since its birth in a Parisian pub more than a century ago, cabaret has always been fashionable. Perhaps it is something to do with its innate ability to reflect the zeitgeist of the metropolis it inhabits. Or, more simply, that it always manages to reinvent itself at the hands of the actors, writers, musicians, artists and poets who adopt its format at any given time.

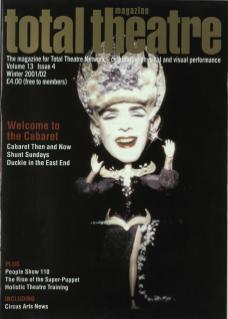

Today the word 'cabaret' is attached to a breadth of entertainment, from pole dancing in nightclubs of the red-light kind to literary soirées. But the beginnings of cabaret were more innovative than the current over-usage of the term gives credit...

The first known cabaret was the Chat Noir in Paris in 1881 where artists and writers entertained with their own songs and poetry in a pub owned by Rodolphe Salis. It began as a spontaneous gathering of like minds but as it grew popular, it became an opportunity for its performers to try out new work for very little or no pay with the chance to advertise it to a wider audience.

The Chat Noir very quickly became fashionable and Salis moved the cabaret to bigger premises. Aristide Bruant, a singer and composer of popular argot songs, then took it over, renaming it Le Mirliton and challenging his audiences with lyrics laden with social criticism.

Interestingly enough, the success of the combination of substance and format could not be sustained and the opportunity for commercialisation was soon exploited by copycat enterprises. Both Salis' venture and Le Mirliton survived less than a decade and what followed were mere shadows, kitsch interpretations lacking in innovation and experimentation. This was to become the plight and also the beauty of cabaret as it developed into the next century; to constantly reinvent itself, to reflect its time but to always keep one step ahead of it.

In Berlin in the late 1890s, a well-known actor, Max Reinhardt, established Sound and Smoke. Initially a weekly social gathering at the Café Metropole, it quickly became popular for its improvised parodies of contemporary theatre, including its tendency to be segregated into mutually exclusive schools of thought such as naturalism and symbolism. Sound and Smoke's supporters were more often than not the very people creating the work that was being parodied – including Reinhardt himself – and even its audience wasn't safe from satire. For instance, 'Ten Righteous Ones', a sketch about ten spectators of various dispositions and humours, such as a late-comer, a critic and an artist, dealt with subjects that are still fine fodder for satirists and comedians today.

But it was all in good fun and more about taking the wind out of the sails of pretentious art and bringing it back down to earth with the simple magic of laughter than any cynical or dismissive exercise. In this sense, cabaret became responsible for injecting new life and vitality into the art of performance.

In 1916 came Cabaret Voltaire. An electric fusion of the legacy of Futurism and the birth of the Dada movement, Cabaret Voltaire took place on an exhausting nightly basis and, not surprisingly, existed for only five months before it burnt itself out. Set in a small bar in Zurich, it was originally the idea of Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings but also attracted the likes of Tristan Tzara, Kandinsky and Frank Wedekind. Evenings of improvised performance would descend into pandemonium with a stage cluttered with music, animal noises, repeated incoherent sound, and movement such as Tzara wiggling his bottom as if it were the belly of an oriental dancer. They called themselves nihilists and, against the background of the First World War, they embodied the disillusionment and chaos being felt across Europe at the time.

But Voltaire's novelty quickly wore off and as Dada's exponents took hold of the material it also became less accessible. The owner of the club issued an ultimatum – 'Offer better entertainment and draw a larger crowd or shut down.' Whilst Dada continued to send shock waves through a post-war sensitive world long after Voltaire closed its doors, cabaret remained the standard-bearer for artistic experimentation that was also entertaining.

Cabarets reminiscent of these artistic collaborations continue today despite the plethora of revues, stand-up comedy and musical recitals which adopt its usage.

In the bustling metropolis of London there is: Duckie, usually to be found at the Vauxhall Tavern; Shunt, in a railway arch in Bethnal Green; the eagerly awaited return of the People Show Cabaret in 2002; and of course, the inimitable Madame JoJo's in the heart of Soho. And, like their predecessors, they are still challenging the contemporary state of affairs – whether sexual politics, society's obsession with celebrity or art itself.

I saw Duckie performer Marisa Carr (aka Carnesky) some years back at the Raymond Revue Bar in Soho. She was working with the Dragon Ladies on their Grotesque Burlesque Revue, a disturbing satire on the power of female sexuality. It was in part a parody of the Bluebeard story, with Carr trussed up in latex oversize breasts, red yawning terrifying mouth for a vagina and a compulsion to suggestively finger its equally lurid 'tongue'. The cabaret's staging in one of London's notorious strip joints was inspired.

Another Duckie member, the inimitable Divine David, an eccentric creation, part drag, part victim of modern living, compered this same evening. His ravaged heavily made-up features and bandaged wrists were nothing compared to the magnificent firework display of acute wit and cutting sarcasm he relentlessly dished out to the audience. This character was the embodiment of cabaret's essence; the creation of artist David Hoyle, the always-avant-garde Divine David became no more when Hoyle called it quits just as success on the murky waters of the mainstream beckoned.

There are also those cabaret performers who work independently of a group and play the circuit, an odd mix of venues and audiences scattered across the country. My favourites are those who are turning preconceived notions of femininity and performance on their heads. The wonderful Flick Ferdinando is one such performer. Many may remember her 'Brown Bag’ act in which the beauty of a brown world is extolled by a brown-wearing, brown beverage-drinking woman on heat. Her more recent 'Hunchback Ballet' is a dubious homage to Fonteyn, in which the dance of the dying swan in Swan Lake is mutilated by an arthritic would-be ballerina.

Similarly, the antics of female sword-swallower and maggot-eater Miss Behave (aka Amy Saunders) are too hardcore for audience members even in these supposedly unshockable times. Not content with a sword going down her gullet, she also pierces her breasts with hospital syringes. I remember having to grin and bear it as I cleared the floor of her ugly wriggling maggot co-stars at a Circus in a Box cabaret some years back as white-faced audience members slowly returned to their seats.

In Starred and Feathered at the Eve Club earlier this year, Rachel Dyer performed a traditional fan dance right down to being 'naked except for her heels'. Proof that a naked woman writhing on stage still shuts an audience of both men and women up, Dyer wiped the leers off their faces as she then proceeded to lay – yes, 'lay' – a golden egg. This act of subversion was further magically enhanced when it took her a good few minutes to squeeze it out. Hysterical and inspired but too disturbing to be classified as populist and too unique to find their way onto the mainstage, such cabaret performers continue to ensure that audiences are fed and watered with thought-provoking and challenging entertainment.

Best summarised by Peter Jelavich in his book Berlin Cabaret as a tease, a phenomenon which simultaneously sustains and satirises the erotic energy of its day, cabaret is still out there, still going strong and remains at the vanguard of live performance.

Anne-Louise Rentell will be producing a new monthly cabaret at Hoxton Hall, starting Thursday 28 February.