1000 revolutions per moment began as a journey into sound.

Periplum’s work has always been influenced and inspired by music, driven by an underlying musicality. We often think of our works as compositions – looking for the emotional rise, the sense of timing, as we don’t tend towards a strictly narrative theatrical form.

We relate our work to that of musicians and composers from lots of genres – Tom Waits, ligeti, Public enemy… With 1000 revolutions we decided to make this music fervour the subject of the work and began thinking of a site-specific piece set around a music venue - exploring the feeling of the life-changing live gig that you don’t forget, that becomes part of the constellation of your most life-affirming experiences.

This was problematic because the task of representing the perfect gig is a lot to ask and music taste is a minefield of subjectivity, so it could be hard work to take an audience with us. So we started to think about the wider impact and associations of music in life – the actions and desires it can inspire, the moments in memory it can represent, experiences it accompanies, friendships it leads us to forge, the creative and destructive fire it breeds, and the blind aspirational force it can unleash.

The title 1000 Revolutions Per Moment was originally inspired by thinking about ian Curtis in the borderline state between ecstatic dancing and the point of fitting, but was also to draw on the social and sometimes political force of change that music can foster – music as a trigger. Since the name and the notion of 1000 revolutions per moment first entered our minds in 2005, the project has spanned a wild medley of imaginary versions and themes – a fantastical biography of Ian Curtis, a multi-dimensional exploration of the ‘perfect gig’, an enactment of the alleged military coup on Harold Wilson’s government, and a real revolution encompassing a city here and now as the show unfolds.

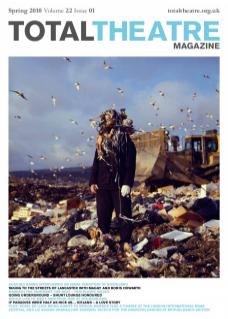

In the early versions, performed in reading and Brighton in 2009, the show became a performance trail trawling the underside of the city. Indoor and outdoor social spaces, boats and bridges, car parks and parks, with music as a key: Beneath the pavement, the beat. This power of music to move us to get up and do something was the feeling that we wanted to evoke, and to allow the audience to feel that they could be protagonists in the action to a certain degree, to feed into the movement.

In the run-up to the show, we invited audience to nominate life changing songs and many of these featured in the soundtrack. A busker along the trail also challenges the audience to name a ‘truly great song’, which led to the beginnings of a debate on the street. As the busker said, this question could start a war.

Music weaves the piece together – a roaming band, the busker (a devil-at-the-crossroads type character), a free party sound-system, mobile box amps, live string recitals on rooftops, guitar feedback/white noise from a passing van, and so on. The characters’ journeys are also driven and accompanied by music. We use music as a vehicle to explore what fuels people and find out what their desires are for the future. We ask, what’s the sound of a city? How does this reflect in individuals in the city, and how do people contribute to the city as a living, breathing symphony.

The show was devised through a series of performance experiments, almost in the nature of happenings – leading on the one hand to near-arrests and on the other to the making of friends. Then there was the social and cultural research into the identity of a locality, and going out onto the street to ask local people Where’s the heart of the city? Plus, new musical collaborations between company artists and local musicians. Finally, developing visual representations – in Brighton, 50 placards carried by the audience celebrated independent organisations and local social identity; in Reading, the show’s visual identity drew on waveforms taken from field recordings to try and capture the heartbeat of the city.

On the social level, we worked with predominantly independent, even subterranean organisations, venues and artistic partners, as these reflected a desire to dig beneath the monoculture of the high street and find the local heartbeat.

Practically, 1000 revolutions is a journey through spaces and so we begin by piecing the trail together, trying to find exciting routes and installation spaces. Key scenes in the piece are adaptable to happen in different orders. Again, we’re looking at the performance with the sense of a music composition.

In Brighton, several audience members said the show was like a love song to the city.

Whilst having a framework for touring, the show is mainly site-specific – from the local participants (up to 40 per city), musicians and venues we work with to the changing geography of the trail and local social and music history we draw on: in Reading, the town as a battleground for the British revolution of 1688 and in present times, its identity cast in the shadows, the town as a gateway to the capital or an extension of London; Brighton as a free party republic or a transient city.

This touring/site-specific dichotomy is a real challenge – it’s almost a case of making a brand new show when we go to a new place. We try to find a similar series of spaces in close proximity to each other and adapt key scenes for these. A scene in Reading where we took the audience on a river barge was adapted to become a scene in an illicit speakeasy when the show went to Brighton. Simultaneously, the live river shanty that was sung on the boat was adapted by a chanteuse for the speakeasy.

Always, music provides a continuum or a sound-clash that gives the piece its inner necessity.

The research and development of 1000 revolutions per moment (2009) was supported by John Luther and South Street, Reading, where the company was in residence in August 2009; and by Donna Close, producer of White Night Brighton, where the show was performed in October 2009. Periplum would like to thank these supporters and acknowledge ‘the freedom granted to explore lots of creative ideas around the themes and lots of ways of engaging the public in the project’.

In 2010 the company are aiming to consolidate these ideas, whilst also ideally looking to add a little more spectacle. They have a smaller version of the project in Kings Cross as part of the Reveal Festival in April, and a larger version as part of Fuse Medway festival in Gillingham in June (see below for dates).

1000 revolutions per moment development supported by Arts Council England, Brighton & Hove Arts Commission and South Street Arts Centre, Reading.

Spring 2010 dates:

Reveal Festival, Kings Cross, London 23–24 April 2010

Fuse Festival, Gillingham, Kent 18–9 June 2010

For further information on these dates and on the company see www.periplum.co.uk