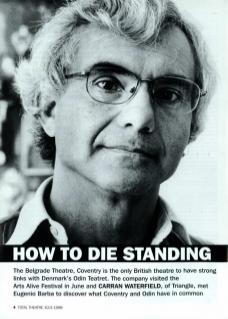

Why you are in Coventry?

In the 34 years that Odin Teatret has existed, the company has developed strong and continuous contacts with individuals and groups who have settled in small centres and tried to develop continuity in their cultural life. Coventry has been among the places we have visited and we have also hosted artists from Coventry in our theatre in Holstebro, Denmark. The first point of contact came with the visit of Bare Essentials Youth Theatre and then, thanks to that visit, the Belgrade Theatre became interested in us and the relationship developed into one of continuous exchange.

What are your plans for future projects in Coventry?

The Belgrade is interested in presenting our newest production, Mythos, in 1999. They want to involve Odin in the city's millennium celebrations. They would like Odin to be among a group of companies who will organise a huge performance involving different aspects of the city.

Have you got any ideas about how this might happen?

What I find interesting in Britain, and of course in Coventry, is that each town has a strong cultural diversity. We would like to find a way to involve Coventry's ethnic minorities in our practice of 'barter', of exchange.

Also, I keep asking myself, what does the end of the millennium mean? What can we show as a sort of farewell to an age which will disappear?

The current millennium has created many enduring performance traditions. For example, Noh, which is the oldest civilised form; Ballet, which is a product of the sixteenth century. What will happen to these traditions in the next millennium? Before, in these old traditions, pupils were taught for fifteen to twenty years to incorporate all the knowledge. Now, this period is shorter. Now what we call progress is in a way becoming the enemy of some of the traditional performance genres.

When I first met you in 1990 you spoke of a unifying factor amongst your actors and called them ‘fighters'. What do you mean by this?

There is one word which can concentrate the experience and history of the Odin Teatret: exclusion. Odin began as a group of people who had been excluded from theatre schools in Norway. As a theatre director, I was myself excluded from directing in normal theatres in Oslo. Being excluded led us, in 1964, to create a company without a venue; which seems as ludicrous today as creating a theatre in water.

In order to resist, we had to invent a mythology, or new models of theatre history which could encourage us to continue. But, at the same time, we were approaching theatre history in a different way: with the eyes of the excluded. We discovered that previous theatre-makers had encountered similar experiences, for example Brecht and Stanislavski. After their deaths, however, they were no longer disturbing. They were transformed into monuments.

It was important at the beginning for each actor to find their own motivation. To work unpaid, we all had to believe that what we were doing was the right thing, despite the fact that we had no audience at that time. We were completely unknown and few people came to see our performances. To endure we had to have faith. Faith that we were doing what we were doing, because we had to. Faith means to consistently realise, every day, a set of simple actions which manifest that loyalty. This is what I would call the generosity of the actor, or being a 'fighter'.

Is this the driving force of your work?

When you have been working like this for a few years, it becomes a reflex which remains with you, even when the conditions have changed. We are much more accepted now and we are privileged because we have our own theatre. We receive a subsidy of up to fifty percent for what we need. We have many spectators throughout Europe who are loyal to what we do. Nevertheless, this reflex which we built up when we began, still remains and is one of the forces which makes us work so hard at finding new fields of activities.

What would you say is your present struggle?

To die standing. This is the challenge. Now that Odin has existed for 34 years, we have accumulated a vast amount of experience. We know that we can tackle many situations. We can go through periods of difficulties and we know that we will keep going. We know this on the one hand, but on the other, there is the inexorable law of nature. Biologically we will get old and no longer have the same force and power. This has an influence on our work, on the process and results.

So, in a way, it is how to remain alive, in spite of the fact that our vital forces are diminishing, which is our struggle. One consolation is to remember those masters of both Western and Eastern theatre who are very old, but who have this capacity to irrigate a particular strength and force when they perform, with out appearing to do be doing anything at all. So I know it exists, this different way of performing, and it is based on a very contained power of expression.

So this is what I mean by to 'die standing': to be able to become very weak physically and to acquire the complementary ways of letting only the essential come through to the spectator.

You have spoken about death. Can you point to one thing which relates to your birth as a company?

This image of dying standing has to do with what you might call the mythology of the Odin Teatret. From the very beginning we desired not to be sedentary but nomadic. We had a ‘tent' and this tent was moved everywhere. But within this tent were all our values, and among those values was something you could call 'honour' or 'loyalty’. We had to give our profession something which could exist beyond the aesthetic or the artistic: something which could transcend our society, or which could become a criteria by which our craft could be judged in our time by our society. So, from the very beginning, this nomadic mentality made us live at the edge of the theatrical map.

Holstebro is a small town in a province in Denmark where we could retire and concentrate on what was important to our craft. We would travel, sometimes welcomed into huge marble palaces, but we knew this was not our place. Our place was always the tent. So we always went back to the tent. So I would say this is what we realise as the end of our trajectory: the feeling that we were born under a tent and that we will die under a tent.

Does this sense of a nomadic existence also connect with the sense of being in exile?

This has been one of the major points of reference constituting Odin's identity: feeling in exile in this society. So this thing about always being outside and having another set of values, has also been the fighting spirit of the Odin. Not because we want a fight, but because our idols are different from the idols of society. But then society is always changing their idols.

Our goals are forever changing too. In 1964 we were discovering the importance of text: then we discovered about not just presenting a text. Next we discovered that politics was very important to us; then we were thinking that a sort of artistic ethos was important in order to build a professional identity. Finally we found that theatre cannot just be about artistic excellence but should also have a social transcendence. Now a sense of legacy has become important for us.

When you have worked your whole life, you have to leave a legacy. This is not what we give to those who come immediately after us, but what will come into the hands of the generation which comes after that which has seen our work.

Is the work you are doing for the millennium a reaction to your sense of marginalisation and isolation?

It is an opportunity to take Odin into a new context, with challenges which are very different to the ones which usually confront us. We have, by definition, to be a laboratory. But in reality, all the laboratory work which is not connected with the work on the actor done in Holstebro – all the social part of the laboratory – has always happened outside Holstebro. Because outside Holstebro we get offers to do special projects.

Has it been a struggle in Holstebro?

When we arrived in Holstebro in 1966 the public reacted very violently to us. We were a Norwegian group, a group of foreigners, and they couldn't understand what we were doing there. In 1966 we used very little text in our work. Besides, we were a company of actors coming from all the different Scandinavian countries. Each actor spoke their own language, and so the Danish spectators could not understand if the actors spoke Swedish, Finnish or Norwegian. So there was a partial break of convention. People were used to going to the theatre to understand text, and they couldn't do that with us.

Plus there was a completely different use of the space. We were not using a stage; actors mixed with the spectators. The story was told through song, movement and actions. It was a very dynamic dramaturgy. However, the spectators were not used to it and they felt insecure.

So all the people of Holstebro, who had never seen theatre before, asked ‘why should we pay money for this?' So for many years most of the syndicates were against us. The Labour people especially were against us, even though the politicians who had invited us to Holstebro were the Labour Party.

But then slowly things started to change, partially because we became known outside Holstebro. Secondly, we organised activities in Holstebro which many people from outside the town attended. In time we became an economic factor in the town. Many firms began to support us, not for artistic reasons, but because we brought business to the town.

Now, after thirty two years in Holstebro we hold a very powerful position. Local institutions will cooperate with us. Any church will open a venue to us if we want to have a concert. Or, if we want to work with the army, there are barracks that will participate in our events. So things are changing.

Not a lot of local people, however, come to see our productions. But mostly they consider us normal and efficient workers. They don't understand us, but they see, from a craftsmanship point of view, we are working hard and these are values, in a small rural place like Holstebro, which are still acknowledged.

For companies in Coventry, the Arts Alive Festival and the Coventry Theatre Network are very hopeful developments. But your situation in Holstebro sounds idyllic compared with ours, is that the case?

Yes, but it depends. I'm sure that if you had a venue here in Coventry where you did a performance three or four times a week, soon people in the Neighbourhood would notice that the thirty or forty people coming to your show every night would maybe have a drink afterwards in the local pub and maybe eat at the local restaurant. Slowly an interest will build. Then after twenty five years, believe me, you will be in a good position!

I'm reinforced in my belief that change happens because an individual provokes it. In the end this situation is up to you. Even if you feel in exile now and that you have only managed to touch the surface, if one looks objectively many things have changed in Coventry.