Have you ever wanted to shout during a play? Perhaps you've felt like expressing your enthusiasm for the show, or maybe you've had some useful suggestions to make about how the company could be doing it better. Of course, such behaviour is taboo in the western theatre tradition where, with the exception of Pantomime, the audience have a passive relationship to the stage. Audiences are expected to sit in silence and wait until curtain call to articulate their love or loathing of a play with polite applause. Theatre etiquette even requires that, should you happen to hate the show you've paid to see, you really ought to wait until the interval to walk out.

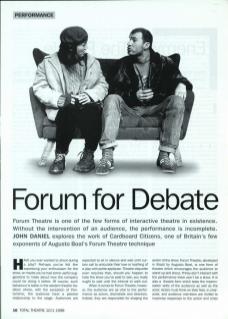

When it comes to Forum Theatre, however, the audience are as vital to the performance as actors, dramatists and directors. Indeed, they are responsible for shaping the action of the show. Forum Theatre, developed in Brazil by Augusto Boal, is one form of theatre which encourages the audience to stand up and shout. If they don't interact with the performance there won't be a show. It is also a theatre form which tests the improvisation skills of the audience as well as the actor. Actors must think on their feet, in character, and audience members are invited to improvise responses to the action and cross the boundary between spectator and performer to become a part of the play.

Cardboard Citizens is a theatre company which has pioneered the use of Forum Theatre in this country. Established in 1991, it is also the UK's only professional theatre company whose members all have personal experiences of homelessness. The company apply Boal's technique to make performances which encourage audiences to participate in the theatrical event. Their shows function as forums for specific communities to collectively explore common problems and concerns. Under the artistic direction of Adrian Jackson, Cardboard Citizens devise plays which explore issues related to homelessness which are performed to homeless communities in day centres, drop-ins and hostels. The work is cathartic both for the company members who participate in the devising process and for those homeless people who see issues of mutual concern presented in the work.

The company devise scenarios for their plays by revisiting real life experiences in the rehearsal room and considering ways they might have handled situations differently to achieve alternative results. These turning points are what Boal calls moments of ‘crisis'. Boal takes his definition of the word from Canton Chinese where it has two parallel meanings: 'danger' and 'opportunity'. By re-enacting moments of ‘crisis', the company aim to provoke their audience into intervening in the action of the play to introduce alternative responses to the situations presented. As Jackson comments, the action creates ‘a kind of hole in which we are inviting people to dive’.

Sometimes we have to be quite provocative to our audience and make it clear that if they don't do anything they'll just have to sit through the same bloody performance again, so it's up to them to make a more interesting afternoon

Diving into the live action of a play takes some guts. The rules are simple: after a short play is performed (usually no more than forty five minutes), the company re-enact it (not necessarily from the beginning), and invite audience members to shout ‘stop!' at key points in the action where they perceive a protagonist could have done something differently. By calling out the audience member commits him or herself to coming onto the stage to improvise an alternative resolution to the scenario presented. Jackson admits that this is often a scary moment: ‘sometimes we have to be quite provocative to our audience and make it clear that if they don't do anything they'll just have to sit through the same bloody performance again, so it's up to them to make a more interesting afternoon!’

But once the ice is broken, it can be hard to keep an active audience down. The question Cardboard Citizens always pose in their shows is 'did it have to be like that?’ And, as Jackson says, ‘If we've done our work right the audience will say, “No, it didn't have to be like that”, with some vehemence.’

The process is entirely unexpected and no two performances of a Cardboard Citizens show will be the same. Jackson instructs his actors to react to audience interventions in a way they think their character would respond on a bad day. He does not intend to give the interventionist an easy time, as he explains: ‘people don't want to achieve a meaningless victory, they don't want to come on stage and just get their way because that negates or minimises the scope of the problem they're dealing with’. In this context, improvisation is regarded as a form of contest. Boal uses a simple physical metaphor to illustrate the point: two people lean into each other and push hard against each other's shoulders, the goal is not for one person to push so hard that the other wins the contest, but for each person to exert equal pressure in order that they end up providing mutual support. As Jackson says, ‘improvisation is not a game to outwit the other person but a game to work with the other person to find out where you can get to’.

The contest in Forum Theatre may appear unequal: the actors are familiar with the script and comfortable on stage, whilst the intervening audience member is entering unfamiliar territory. However, the audience member has the advantage of knowing what the purpose of his or her intervention is, whereas the actor has to respond to each new one spontaneously. In balance, the contest is actually equally weighted. Anyway, the whole point of the exercise is to generate conflict and debate in order to reach a point of resolution, as Jackson says: ‘people want you to fight back and we do fight back’. Just like in real life.

In fact the question of where the boundary lies between real life and fiction in this type of theatre is an interesting one. Firstly Cardboard Citizens' shows are liable to touch on some highly emotive issues. They have to in order for the process to work. As Jackson admits, ‘every time anyone intervenes it's for a deeply personal reason’. However, he is quick to insist that Forum Theatre in no sense provides a therapeutic function. Although it's true that ‘people do involve themselves heart and soul’ in the work, and that ‘it takes a lot of courage to do so’, Jackson maintains that the process involved in Forum Theatre is not individualistic (like therapy) but societal; problems are solved by the group not the individual. To push home the point he explains that he's ‘never encountered a situation where people arrive at a place they didn't want to arrive at’. Plus, unlike in other types of improvised roleplay, Forum Theatre has a sort of director who presides over the proceedings.

This figure, known as the 'joker', is responsible for mediating between the individual, the audience and the stage and assumes an impartial role. The Joker will intervene if an intervention is getting out of hand, but he or she is not there to provide judgement. Nevertheless, Jackson does concede that audience members will often intervene and treat their interlocutors as people from their own lives. At these points, the improvisation might potentially veer radically away from the narrative of the play and it is up to the actor to decide whether to run with the new material or not. It is a hard job for the actors, who have to keep their wits about them at all times. The play is being rewritten and developed continuously and no two interventions are alike.

But surely as each performance is an improvisation around the same set of givens, actors must begin to be able to predict and pre-empt interventions? Jackson says not: ‘an intervention may look like a previous one but it is in fact completely different’. The actor must be attuned to the individual nature of each and every intervention.

Is there a danger of this sort of theatre being worthy? Or, worse still, patronising? Unlike theatre in education, Forum Theatre does not set out to proselytise. The only lessons to be learnt from a performance are the ones which the audience create for themselves. The audience create and shape the debate; Forum Theatre merely acts as a trigger. Jackson refers to the process as a way of getting people to talk very actively about stuff in a very enjoyable way. ‘We are not trying to inspire anything apart from a lively theatrical debate,’ he says. ‘Preferably resulting in a certain amount of information being exchanged; a certain amount of empowerment if you like.’

Jackson's three basic rules of performance sum the purpose of Forum Theatre up: ‘run with anything, make no judgement and eke stuff out of people at every opportunity’.