We started this year with a reflection (in the editorial of Volume 22 Issue 01) on the nature of reviewing and the role of the theatre critic. I make no apologies for coming back to this subject, particularly in the light of a recent project developed by Total Theatre Magazine in collaboration with PANeK (Performing Arts Network Kent). Writing Performance was a pilot project for those wishing to write about theatre, led by members of our editorial team, and documented in this issue. We are hoping very much to repeat this programme in association with other arts organisations, higher education institutions, and venues around the country – so watch this space.

At the core of our work here at Total Theatre Magazine over the past three decades has been the notion that the distinctions between artist, curator, critic, and cultural commentator are a lot more fluid than some would have us believe; and that theatre-makers could and should be encouraged to write about their own and other’s work – it being a job ‘too important to be left to professional theatre critics’ as Beccy Smith says in the Writing Performance ‘reviews special’ in this magazine. It is interesting that it is considered the norm for a fiction writer to review another writer’s novel, yet is somehow seen as ‘too close to home’ if a theatre-maker reviews theatre. Hence, the almost across-the-board supremacy of the ‘professional critic’ (i.e. a critic who is not also a theatre-maker) in the national press – honourable exceptions like Brian Logan excluded.

Of course there are issues around how one writes, especially if writing about people you may well end up working with in some capacity at some future date, but perhaps that might make for more compassion and a general desire to offer constructive criticism?

As regular readers will know, we now carry most of our reviews on the Total Theatre website (www.totaltheatre.org.uk/reviews) freeing up the magazine pages for a rather different take on ‘reviewing’. For example, in this issue we have Forced Entertainment’s The Thrill of It All reviewed twice, by different writers at different venues. I was interested in seeing what the two reviewers – both theatre-makers themselves, but thirty years apart in age and experience – would have to say. Their responses are, of course, different – all reviews are a subjective response – but there is some shared territory, particularly in the concerns about how ‘radical’ the work seen was. This raises an interesting discussion point: how much ‘repeat’ of ideas/themes/structures is acceptable in new work? Are we harder on theatre-makers than we are on artists working in other forms? (Murakami’s novels almost always feature girl runaways, boy suicides and cats, for example!)

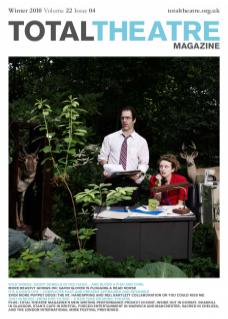

Regardless of subjective views, I’d have thought that a key ‘rule’ to reviewing would be that you have to review what was witnessed, rather than what you thought ought to have been presented to you. I was rather confused by Michael Billington’s review of the Handspring/Neil Bartlett collaboration Or You Could Kiss Me (in the Guardian) in which he wonders, why puppets rather than actors? Surely the answer is: because it’s puppet-theatre – that’s the form, and the chosen art and craft of the people making the work. It would be a bit like seeing a dance piece and asking ‘why does it have dancers in it?’ No such problems with the puppets in our review of that show, which you’ll find in this issue.

Being There – in which we invite artists/company members to ‘review’ their own show in tandem with an outsider’s view – is now an established feature of this magazine, and in this issue it’s the turn of Stan’s Cafe, with Tuning Out with Radio Z at Bristol’s Tobacco Factory Theatre.

The Works is a new regular feature and another take on the question of how to write about theatre. It’s a personal view of a body of work by one artist or company, in this case Complicite as seen by Richard Cuming, who is viewing their work from the perspective of someone also working with ‘contemporary clown’.

Also on Complicite: we’ve placed side-by-side reviews of two of the three different shows directed by Simon McBurney that have been playing in London this season (November – December 2010): Shun Kin at the Barbican and ENO’s contemporary opera, A Dog’s Heart.

Elsewhere in this magazine, you’ll find a reflection on Total Theatre Award winning show Roadkill; an artist’s diary by Gavin Glover of Faulty Optic, who brings Flogging a Dead Horse to the London International Mime Festival 2011; and in another Mime Festival related feature, Geoff Sobelle (co-star, with Charlotte Ford, of Flesh and Blood & Fish and Fowl) is our candidate for Voices.

Plenty to get you through the long winter’s nights, so enjoy!