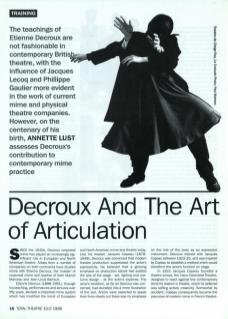

Since the 1940s, Decroux corporeal mime has played an increasingly significant role in European and North American theatre. Artists from a number of companies on both continents have studied mime with Étienne Decroux, the 'master of corporeal mime’ and teacher of both Marcel Marceau and Jean-Louis Barrault.

Étienne Decroux (1898-1991), through his teaching, performances and lectures over fifty years, devised a corporeal mime system which has modified the trend of European and North American mime and theatre today. Like his master, Jacques Copeau (1878-1949), Decroux was convinced that modern theatre production suppressed the actor's expressivity. He believed that a growing emphasis on production values had exalted the arts of the stage – set, lighting and costume design – at the actor's expense. The actor's rendition, as far as Decroux was concerned, had dwindled into a mere illustration of the text. Actors were expected to speak their lines clearly but there was no emphasis on the role of the body as an expressive instrument. Decroux trained with Jacques Copeau between 1923-25, and was inspired by Copeau to establish a method which would transform the actor's function on stage.

In 1921, Jacques Copeau founded a theatre school, the Vieux Colombier Theatre, designed to react against the contemporary trend for realism in theatre, which he believed was stifling actors creativity. Somewhat by accident, Copeau consequently became the precursor of modern mime in French theatre.

In his school, Copeau introduced mime exercises with a mask to encourage the actor to rediscover the expressiveness of the body. He revolted against a theatre which conceived of the actor as a slave to the text. He emphasised the use of movement to enable the actor to express the text to the fullest. His stylised productions achieved a dramatic poetry which the theatre of his day had lost.

For Decroux, Copeau's exercises with masks became an end in themselves and he sought, through a theatre solely of mime, to make the actor's art autonomous. Although Copeau's theatre has not survived, its spirit lived on in the avant-garde movement, most notably in the theatres of the Cartel (Baty, Dullin, Jouvet, Pitoeff). With these stage directors, the actors art was developed and his body well trained. Even those who were most respectful of the text, utilised all the visual resources of acting enriched by new uses of movement, design, light and colour. These stage animators helped to revive the art of movement and the visual values within the spoken theatre.

Decroux aimed to find, through the body's movement alone, a pure, autocratic expression of a complete dramatic form. To achieve this, he made use of exercises with a mask, because his aim was not as yet to perfect the dramatic art, but first of all to make it an art. In his words, ‘dramatic art, until it is an art, cannot become a better one’. Decroux believed that through mime, the actor could free himself from the tyranny of the other theatre arts. Working unsupported, with nothing but air and silence around him, the actor could learn to centre in a medium which was complete, and as Raoul Gelabert said in 1959, ‘containing in its essence all the arts’.

Decroux proposed that actors would only be ready to join forces with other theatre artists – designers, composers, etc – once they'd attained mastery of their own bodies. Then, he believed, actors could subordinate the contribution of other theatre artists to their own. In this way alone could the actor’s plastic expression fuse with the spoken text, and their art, inspired by painting, sculpture or poetry, reach the same level as those other arts.

But what is the contemporary value of Decroux's mime training? In addition to opening new vistas for the mime performer and codifying his art, Decroux contributed greatly to the art of the actor. In his view, body training was essential for both mime and actor. Just as manual work balances intellectual development, endowing thought with common sense and order, so training in mime also forms the actor. While his students developed their imagination and creativity through exercises in mime improvisation, they also worked for strength, concentration, flexibility and control. ‘The essential aspect of my art,’ Decroux said, ‘is articulation. Thanks to it the body becomes analogous to the piano keyboard. Our art is like chemistry and music. To succeed at it requires daily study for three to four years. Those who embrace with fervour the formula to work from the inside, must become aware that what comes from the inside must arrive at the outside.’

Among the many mimes who studied with Decroux in Paris were Jean Asselin and Denise Boulanger, who began a mime school and their company, Omnibus, in Montreal, Canada in 1970. Their repertoire moved from corporeal mime pieces (Lover's Duets, Water) in the 1970s, to Beau Monde (1982) which juxtaposed mime, dance and their first utilisation of dialogue in a work depicting family and social alienation, the distortion of sex, the futility of war, etc. In their Cycle of Kings (1988), a satirical adaptation of Shakespeare's Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V speech and movement were closely integrated, the movement bringing other meanings to Shakespeare's text.

Gilles Maheu of Montreal's Carbone 14, who trained with Decroux trainee Yves Lebreton, performed with the latter in a corporeal mime piece, Hamlet Machine, which combined mime, dance, puppetry and acrobatics with dialogue in French, German and English and video of war scenes, to portray a modern day Hamlet as an absurd hero in a world filled with disillusionment.

American corporeal mime, Daniel Stein, who performed and taught in Paris before relocating to the dell'Arte Players in Blue Lake, Califomia, developed from his Decroux training one of the purest most poetic movement expressions in Timepiece, premiered at the Milwaukee Mime Festival in 1978. Here Stein portrayed the passage of time in a man's life, moving from one sculptured attitude to another, with a body which resembled that of a statue of a Greek athlete. By 1989, in his autobiography Windowspeak, Stein contrasted American, French and Japanese life through corporeal mime, acting techniques, the animation of objects and a spoken text.

Steven Wasson and Corinne Soum, former Decroux assistants, who moved from Paris to London in 1995, are among those who have remained Decroux purists. After creating non-verbal corporeal mime pieces in 1981, they founded their Ecole de Mime Corporel Dramatique in Paris in 1984 and their company, Theatre de l'Ange Fou in 1986. La Croisade, performed at the International Festival of Contemporary Mime in Winnipeg in 1985, did fuse voice with corporeal mime around the themes of a young girl's journey into the realm of memories, illusions and the search for an identity. Aside from creations containing a vocal component, they have reconstructed pure mime works from Decroux's repertoire over a fifty-year period in The Man who Preferred to Stand, performed at The Philadelphia Movement Theatre International Tribute to Decroux in 1992 and 1993; the Mimos Festival in Perigueux, France in 1994; the Theatre de Ranelagh, Paris in 1994; at the London International Mime Festival in 1995, and throughout Europe.

Beginning with Decroux corporeal mime, these artists and many others have gradually added a text and other theatre elements to a solidly based corporeal expression in which the mime creates with their own instrument – their bodies – to then enrich this expression with other theatrical means. And rather than remain merely the interpreter of the playwright, or the adjunct of the set, costume and lighting designer, for instance, the actor is able to master their own craft.

Decroux corporeal training has not only given birth to a renewed interest in the art of mime but it has revitalised twentieth century theatre and re-established the actor's art as a total and complete one.