I'm part of an audience who are sitting on raked seats watching a performance by IOU. It's taking place in the car park of Nutclough Mill, Hebden Bridge. The company have built a little garden with the clutter of tools, a cabbage patch and various other plants and vegetables Further back, the ground dramatically falls away and there is a garden shed perched over the drop. A balcony on stilts at the back overlooks this chasm. The shed is reminiscent of a lot of buildings in this part of the country where you have the steep sides of a valley to build on. In the distance is a big horseshoe of houses on a hill.

The performance concerns a couple who live in this shed. From time to time they are visited by a remarkably persistent salesman. One time he brings a large carpet to sell – there's a bit of haggling outside but eventually the three enter the shed to fit it. You can see them through the windows as they work; there's an occasional frown when it's not quite right, and soon the salesman appears at the back to see how it looks from a distance. He keeps moving backwards to get a look. He's getting uncomfortably close to the edge of that balcony. By now, the audience is a bit on edge. On the one hand, they hope he's not going to do what they think he's going to do – but on the other they hope he does. He does! And when he does lean back so far that he tumbles off the back of the balcony and plummets out of sight, the whole audience sits up and the raked seating feels like it has lurched forward several feet.

This performance, The Sea Saw Red, took place in 1984, but writing about it now I can remember every detail vividly. Indeed, when I toured with IOU in 1989 there were a lot of people who came up after shows and described, just as I have done, bits of shows they'd seen ten years earlier, in extreme detail. This for me is what makes IOU such a special group. Their performances can be very opaque and you can struggle to find meanings in what they do but images and actions are presented in such clarity that they impress themselves on your imagination.

In 1994 they presented Boundary at the Horniman Theatre in Manchester. The show travelled through time, and in the main section we witnessed the gradual disintegration of a decadent court. As the king and his courtiers listlessly went about their slightly pointless daily routine, a procession entered from the side. It featured a princess, wearing bizarre shoes that inhibited her walking, plus her small retinue. They travelled round the front of the stage unseen by the king and remained standing still to one side until the show finished. In one magnificent stage image we saw the next in line to the throne patiently waiting for her chance; we understood that the king's days were numbered, and we went forward in time to realise that the princess-in-waiting was probably doomed to repeat the mistakes of her predecessor. It was a fantastic example of how the use of space and the positioning of performers can conjure up rich associations. The audience hung on until the last weary throb of synthesiser ended, and then erupted in applause. I have to say that Boundary is one of the best pieces of theatre I've ever seen.

The company were formed in 1976 by members of Welfare State who wanted to develop theatrical ways of combining images and music. The core team were Louise Oliver, Lou Glandfield, Dave Wheeler, Steve Gumbley, David Humpage, and Colin Wood who left in the early 80s, to be replaced by Jane Revitt. This line-up remained constant until the mid 1980s when a more flexible approach to who created the shows was found to be necessary as core members left to pursue other avenues of work and life. Now only Dave Wheeler remains as a permanent member and other artists and associate members are brought in where appropriate (which is how I ended up working on two shows – Gravity, a mid-scale touring show in 1989, and Cure, a large site-specific show in 2000/2001).

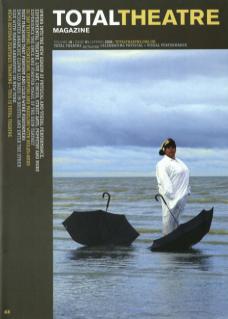

Over the years, IOU have created site-specific and touring work for a wide variety of locations – beaches, deserted houses, woodlands, cellars, mills, car parks, lakes – as well as art centres and theatres. A lot of their work involves adapting an unusual space into a theatre space. A Second Soaking was a commission for the Manchester Festival in 1986. For this they turned an old market-hall into a beach with a lakeside setting and sat the audience on raked seating. They returned to the same venue in 2001 to present Cure for the X-Trax festival. This time, they installed a series of hospital rooms contained in big marquees. Cure involved a promenade performance and a use of different spaces that aimed to disorientate the audience.

Their working process involves trying to keep meanings as open as possible and to avoid tying things down too early. A collage of images, music and poems start the ball rolling. If it's a site-specific piece, then the possibilities of the site are also incorporated into the working process. The company specialise in strange mechanical gadgets (both large and small), costumes that have a strong sculptural presence, masks, and puppets. Video and film are also used to expand the dimensions of the world the company has created. To begin with, the choice of objects and images is largely intuitive and informed by the company's experience or the previous show. As work progresses, interesting and unexpected connections start to make themselves felt. This refusal to pin things down and explain what they are could be construed as deliberate mystification, but it seems apt for work which delves into the subconscious and creates dreamlike connections. When their shows fail it is when they have closed down their options too soon and inhibited all the possibilities: Daylight Nightmare featured a wonderful opening image – half a stretch limousine rammed into a huge framed mirror – but the rest of the show failed to develop or escape from such a startling beginning.

Music is an important element: either composed as the show takes form, or sometimes a previously written song can form the inspiration for a scene. Early shows featured a viola/violin, cello and piano trio, and played a sort of chamber music which seemed exactly right for the intimate, almost introverted theatrical world the company were creating. The incorporation of musicians such as Clive Bell into shows like Boundary and Court in the Act have expanded the musical frames of reference, and the company's last show, Tattoo, featured manipulated noises and rumblings from Dan Weaver – a far cry from the almost classical feel of earlier performances.

The performances are largely free of dialogue. In early shows poems by Lou Glandfield or Louise Oliver would be set to music and sung. In the early 80s, Lou would often tell a long shaggy dog story, the elements of which would occasionally have some connection to the performance, but usually didn't. To me, they were ways of using words as another textured layer of the performance rather than being the only way of conveying meaning. A couple of shows were just his monologues, but they somehow managed to give you the same experience as a performance with more performers and elements in it.

The company is 30 in 2006. It's shameful that so many of the books written on performance fail to mention IOU. Perhaps the authors of these books are intent on following their own academic agenda rather than accurately documenting and reflecting upon what has happened? Had that been done, then surely IOU would have gained their rightful place as one of the UK's most impressive and influential groups.

Edward Taylor is co-artistic director of Whalley Range All Stars. See: www.wros.org.uk

IOU's latest show, Waylaid, is now being reworked for touring in autumn 2006, when the company will also be launching a professional development programme for young practitioners. Please contact Richard Sobey, executive producer at IOU, on richard@iouproductions.com For details of these and other projects see www.iouproductions.com