When did we start? I met Boris when I was doing Fine Art at Reading University. There was a seminal event when John Arden and Margaretta D’Arcy lived in Kirby Moorside in Yorkshire in the 50s, where they had a month-long open session where shows were made. They were very hands-on and immediate in their approach to making theatre. I wasn’t there but Boris was there, John Fox was there, and that’s where they first met. They liked Boris because he was very good at folk music, including many ethnic styles. He was a useful person; he could improvise and make music for a lot of the writing that John Arden was doing – very much a ‘let’s do a show tonight’ sort of thing.

I worked with them because I was a useful art student who could make things. We helped with the first production of The Royal Pardon at the Beaford Centre in Devon. It was a very nice, privileged situation and great fun. Boris did the music and we met Maureen Lipman who was in it. We did two more shows with John and Margaretta, which for me was an incredible training and apprenticeship. We worked for practically nothing and learned one hell of a lot.

The music, the writing of songs and the attitude to performance was very direct and exaggerated for clarity. I had to make big props and masks. It was great as I was fed up with being a fine art student doing constipated paintings with too much agony – great to let rip and make big things. So Boris and I were a team.

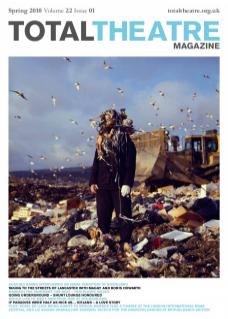

When we went to Lancaster (where Boris went to university) in the 1960s we’d got a start into theatre and the kind of theatre that was very direct. At the time there was a lot of uptight theatre which didn’t appeal to us very much; OK for the initiated but otherwise too precious. The catalyst for us making the Lancaster Street Theatre were the shows we did with Adrian Mitchell, who was at that time the poet-in-residence at Lancaster University (and subsequently a life-long friend). He ran the Song Workshop where he got people writing songs and making music. Lots of people got involved and out of that came shows which were put on in Lancaster. One of these was called The Hot Pot Saga. It was about the Yorkshire/Lancashire wars but in a modern context. With Adrian being political and involved in protesting, a lot of stuff about the Vietnam War crept into it, which gave us an edge. The political edge was always important; to make comments and state the case for peace.

We went on to make a show, called Lash me to the Mast, which was a changing point for me. It happened at this nice old place called the Grand Theatre – a stone’s throw from where we lived in a backstreet terrace in a deprived area of Lancaster. We were very conscious of the social context of where we were – deprivation, problem families, and people having quite drab lives. The contrast between that and the show we were helping to put on was evident. It was a great show but had less edge, less reason to be. For some reason we decided that this should be a free show and the result was chaos. A fairly indulgent student review with some nice stuff in it with all these kids from the neighbourhood belting up and down the aisles. They loved it; they could get in for free and they watched it every night. They were running amok, not paying attention, and it was at this point that Boris and I thought we must make a different sort of theatre that works on the street.

There wasn’t much street theatre at that point. Bread and Puppet were there and I think Red Ladder were doing marches. What we were going to do was make simple direct shows, and we were going to try things on the street. We had no money; Boris and I funded it completely. The question to answer was ‘In a rough neighbourhood how could we make a difference?’ We were trying to make new forms using loud street music, exciting drumming and performance. There was no one to teach us so we thought: let’s just try it, then come back and talk about what we thought went well, what was awful. And then we’d try to do another one. We did one every week – very quick and rough stuff. Not having any acting training was probably a good thing.

Boris got a samba band together – there was a guy called John Hall who had lived in São Paulo who taught us the basics. We had loads of drums, acquired through scrounging, and Boris used to run music evenings where everyone bashed the hell out of these drums. Then we got disciplined and started to put the breaks into the rhythms. So we would march around the streets with this very noisy band – cowbells, shakers and drums. It was pure rhythm and so was like the Pied Piper, attracting kids from far and wide. We never intended it to be children’s theatre, but we were immediately engaged in trying to keep their attention. We would tell stories which involved simple messages about how things could be better.

We would have a circuit of about four venues and go from one to another performing a 30-minute show comprising two or three little playlets. The shows used words – Boris was responsible for them, though sometimes we’d improvise and at other times they’d be written down. There was a lot of music, slapstick and tumbling (for those who could do it). We’d get to a piece of waste ground, defend our space, park the instruments, make the kids sit down if we could, try and get rid of the dogs, and start the show. We used a lot of material in those days – I remember making body heads which were like a Punch and Judy show with large heads that came down to the knees. Very photogenic as they went along the streets. The programme of work fitted into the summer holidays as the people doing it were students – those who had time and who could live on little money.

We were very popular and became what I call ‘social elastoplast’, so the council gave us money to run New Planet City. They gave us £6000 a year, so we moved into a building which was an old engine shed. It was enough for one wage, which we both lived on. We ran week-long sessions for kids and anyone in the community. All day long and then we’d do a show in the evening with the kids in it. I can’t imagine how we managed it because it was killing. We didn’t do this alone – there were about fifteen other people helping us. Funding for community theatre, or indeed any kind of community art, did not exist at the time so we were pioneering a whole change of focus with no money to do it. Pretty groundbreaking stuff. We weren’t sure how far we were trying to change society or make art, and trying to do two at the same time was difficult. We did have a concept of participation in the shows, but wanted to make the shows worth watching in an artistic way, not just to keep the kids happy.

People still come up to me and say ‘I remember when Boris drove the burning car into the river’. It was an event for New Year’s Day. We discovered a local stuntman who told Boris how to do it. We got an old banger – there were petrol cans in the boot, so the flames would trail out the back – and with the fire raging he had to hit the ramp at 50mph in order to shoot the car right out into the river. It was weighted so that the car would hit the water flat-on instead of nose-first. He was strapped in and had to undo the straps when he was underwater and get out. There was no rehearsal – he hadn’t even tested the bloody straps and it was only when he was revving up that he realised how insubstantial the ramp was. Someone had been detailed to make the ramp and that was what he got. Fortunately he hit the ramp (he was a bit lucky was Boris… most of the time) and it worked and was very spectacular. People were screaming in anticipation!

That was the Old Year and after all the fire and smoke a beautiful white raft came across from the other side of the river. I seem to remember making a silvery costume for this gorgeous young blonde teenager who was the New Year. There was a lovely New Year song that we did as a round to accompany this.

Another event was a battle on the river with big boats that we got from the army. We had a battle between the Sun God and a Demon King. Loads of kids had been helping to make all this stuff, painting up the boats and shields and then there was a real battle. We got away with murder in those days. Health and safety? All these tough little kids – we did have something to fish them out of the water when they fell in. These events were exciting, daring and naughty which appealed to the roughneck little kids – and not so little either; you could count on some big naughty boy to do some daring things for you.

The energy consumed was huge and it had to come to an end as our spirits were broken by it all. We took on a big ruined building which needed a lot of money and it was too much trouble. There was a YMCA and a lad’s club in the town, but otherwise nothing else so we became a honeypot for all sorts of problem people. We were always open; we didn’t have a closed-door policy. Hopeless idealism! We tried, but when you’re artists at heart, to try to turn yourselves into fundraisers and administrators is soul-destroying. It needed to change and we left.

The next stage was joining Welfare State – but that’s another story…

Maggy Howarth was interviewed by Edward Taylor on 21 November 2009.

Boris Howarth died on 11 April 2009. His work with Welfare State can be found on their archives www.welfare-state.org. His work as a stone-carver can be seen on www.borishowarth.co.uk. Maggy Howarth’s recent mosaic work can be found on www.maggyhowarth.co.uk