‘I'm in mourning for my life,' says Masha at the very beginning of Chekhov's The Seagull. ‘Take up the body,' says Fortinbras at the very end of Hamlet, as the corpses start to stack up around the stage. 'Fade to blackout’, says the stage direction at the end of innumerable plays. ‘Theatre: The Dying Art', cries the headline, as another company folds and disappears.

It seems to have been a year for dying, this year. Perhaps it's the millennial madness, making us all too aware of our mortality, reminding us that time's marching on, and that the future is running faster and the present's running out. Death seems to be everywhere – in the newspapers, on the telly, on the streets. My mother phoned me up the other week to ask if I thought she should be cremated so that we could all have a separate little bit of her in a pot, to keep. My dad's been joking about the heat it'll take to melt his new steel knees. The spectacular performance of the Queen Mother's birthday was just another reminder of the build-up to the cultural shut-down planned for when she finally sets-off on the big walkabout in the sky.

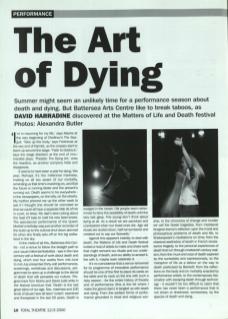

In the midst of all this, Battersea Arts Centre – not a venue to follow the straight path to your usual millennial festivities – saw in the new century with a festival of work about death and dying, which over four weeks from mid-June to mid-July presented thirty-odd performances, screenings, workshops and discussions, programmed to open up a challenge to the denial of death that still pervades our culture. Programmers Tom Morris and David Jubb write in the festival brochure that 'Death is the last great taboo of our age. Sex, madness and 100 kinds of abuse have all been "outed", examined and therapised in the last 50 years. Death is wedged in the closet. Old people seem determined to deny the possibility of death until the very last gasp. The young don't think about dying at all. As a result we are panicked and unprepared when our loved ones die. Age old rituals are dusted down, half-remembered and creaked out to say our farewells.’

Against this apparent inability to deal with death, the Matters of Life and Death festival invited a host of artists to make and share work that might reinvent our rituals and our understandings of death, and our ability to accept it, live with it, maybe even celebrate it.

It's no coincidence that a venue renowned for its programme of innovative performance should be one of the first to place its cards on the table and its neck on the line with such a risky season – for the entire history of theatre and of performance (this is the bit where I make the grand claim) is tangled up with death and dying. From the earliest forms of performance grounded in ritual and religious worship, to the chronicles of change and murder we call the Greek tragedies; from mediaeval liturgical drama's reflection upon the moral and philosophical problems of death and life, to Shakespeare's meditations on time; from the classical aesthetics of death in French renaissance tragedy, to the personal experiences of death that run through nineteenth century realism; from the muck and ooze of death explored by the surrealists and expressionists, to the metaphor of life as a detour on the way to death poeticised by Beckett; from the reflections on the body and on mortality enacted by performance artists, to the contemporary fascination with escaping death through technology – it wouldn't be too difficult to claim that there has never been a performance that is not driven or shadowed, somewhere, by the spectre of death and dying.

But wait! Don't get depressed and turn the page – maybe this is a good thing. Maybe this is exactly what theatre and performance are all about. If death is currently subject to the kind of horrified repression that once characterised sex, then perhaps performance offers us the opportunity to confront and explore our own mortality, and to think of ways of marking death in better rituals than a swathe of black and a few ham sandwiches. Maybe the reason that companies as diverse as Theatre de Complicite, Frantic Assembly, Improbable, In Situ, Edible Theatre and my own company, Fevered Sleep – to name but a few – seem so obsessed by death, is because we have all realised that at the end of the day, it is the only thing that's guaranteed. And maybe performing death brings us all closer to understanding the meaning of life.

It seems to have been a year for dying, this year. Perhaps it's the millennial madness, making us all too aware of our mortality, reminding us that time's a marching on

One of the ways in which theatre brings us closer to contemplating death, is by forcing us to deal with loss. Like life, performances only exist for a limited period of time, after which they vanish, never to be identically repeated or regained. These were the themes that Fevered Sleep explored in our recent project (made for the BAC festival), Exquisite Moments and Imperfect Endings. We were interested in exploring how the very formal aspects of live performance are linked to living and dying. Like life, performance speeds through time, from an awkward beginning (‘how do you start a piece that's all about endings?' we asked ourselves every day in rehearsal) to an inevitable ending. Like life, performance is peppered with moments of beauty, stretches of boredom (we all know that one), exhilarating journeys and tragic loss; and no loss more tragic than the one that happens every night as the lights begin a long slow fade to blackout, the performers clear the stage, and the audience clears the theatre, leaving an empty silence hanging in the air.

This is one of the most profoundly valuable aspects of live performance, this existence in real time, and I can't help but wonder what effect the technologies that are encroaching on theatre (the mandatory video insert, the multimedia spin) will have on it. I don't want to be reactionary, but I think the obsession with new technologies is a way of absorbing that which is most threatening to live performance – if you can't beat them, join them, or better yet, get them to join you. Maybe we can afford to be more reflective, more cautious, to celebrate the loss that marks live performance (as it isn't preserved on film) rather than denying it. Unlike film, unlike digital media, unlike the quirky avatars that dance across the CD-ROM, theatre brings us eye to eye with living bodies, with other human life, with the warmth and the poetry of the flesh. And these performing bodies are bodies that every night, at the end of the show, we have to applaud and lose, that disappear into the memory and into the heart. I can't be the only one who cries when something is so good that it's just too unbearable when it ends.

So maybe we can find in live performance a poetic, an embodied, a profound means for us to prepare for death – for our own deaths and for the deaths of those we love. Perhaps theatre can tell us things about mortality that cannot be explained any better anywhere else (as the festival at BAC seems to suggest) – and, if after two and a half millennia, performance can still find fresh ways of contemplating death, this certainly seems to be the case. And maybe, in enabling us to reflect upon dying, upon our own inevitable and inescapable endings, live theatre and performance can help us to find better, more exciting and more valuable ways to live.

‘Dying is an art,' whispers Sylvia Plath, as the gas caresses her face, ‘and like everything else, I do it exceptionally well.'